When the 27-year-old partied at the multistory, glass-walled nightclub he owned in a region called Kokang, he’d throw crisp Chinese yuan bills into the crowd as international techno DJs, chauffeured in along dirt roads, performed their sets.

In November, the good times rolled to a stop. Wei’s social media presence vanished. He soon appeared in a different kind of video: reading a scripted confession while in Chinese custody.

“The money we make from cyberscams comes from the pensions of everyday Chinese people,” Wei said, a baggy gray sweater replacing his bespoke blazers. “This time, the Chinese government has made up its mind. … We must not cling to any illusions.” Within weeks, his uncle was in cuffs on a plane to China, flanked by dozens of police officers.

The detention of Wei and at least 15 other alleged senior crime family members and their associates was lavishly covered by Chinese media, designed to showcase Beijing’s reach. This was proof, Chinese officials said, of their determination to crush transnational criminals victimizing their citizens, no matter where they are based.

The official Chinese Communist Party news outlet called the arrests a “death knell” for the scams, which tried to dupe people into giving up their money including through bogus investments schemes and fake online romances. “No matter how … big you become,” the People’s Daily wrote, “you cannot escape the severe punishment of the law.”

That crusading narrative is incomplete, however.

A Washington Post investigation found that Kokang’s criminal networks — principally led by the Wei, Bai and Liu families, according to U.N. officials, Chinese court records and analysts — had for more than a decade enjoyed close relations with Chinese officials, primarily in neighboring Yunnan province, along with support from Beijing and the military government in Myanmar. The Myanmar military chief, Min Aung Hlaing, further solidified the families as political and economic brokers after taking power in a 2021 coup.

Evidence of the Kokang families’ deep cooperation with Chinese state officials has partially been scrubbed from the Chinese internet and social media but some of it was archived and verified by The Post. Statements, news releases and photos on the official websites and social media pages of the Kokang authorities, and the Myanmar and Chinese governments show that they worked together on multiple economic projects worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Kokang is effectively off-limits to journalists but video footage, photos and interviews with more than two dozen people who had worked in Kokang offered a window into the more than 300 scam compounds operating in a region that the United Nations estimates tens of thousands of people were trafficked into. That made Kokang a key hub in what Interpol estimates is a $3 trillion online scam industry operating in different parts of the world.

Workers, mostly Chinese nationals or ethnic Chinese, were bought, sold and traded; and then beaten, tortured or killed when they didn’t reach financial targets or tried to escape, according to firsthand accounts, in some cases supported by verified video footage, photos and screenshots of text messages supplied by victims. The Post also reviewed Chinese court records and found more than 1,100 criminal cases linked to Kokang, some specifically to the compounds and businesses operated by the three clans, over the past decade. Almost all focused on low-level operatives involved in illegal gambling, human trafficking and narcotics, the records show, while the heads of the families continued to work with Chinese officials.

The Kokang families, which ran both legitimate and illicit businesses, often from the same property, were useful partners and guarantors of stability as Chinese leader Xi Jinping pursued his massive Belt and Road Initiative, a $1-trillion bet that infrastructure projects along China’s border and beyond would build regional and global influence. Being Han Chinese, the families set up companies in China and obtained identity papers usually reserved for Chinese nationals, corporate records show.

As recently as May 2023, the Lius, for instance, were distinguished guests at a high-profile China-Myanmar border trade fair promoting “mutually-beneficial cooperation,” held in the Myanmar capital. The Lius’ company had a booth alongside Chinese firms such as Huawei and China Telecom. Chinese officials such as the ambassador to Myanmar and the governor of Lincang in Yunnan province were also present.

That umbrella allowed the clans to lord over Kokang, a majority ethnic Han Chinese region, and turn it into the center of a sophisticated criminal network that generated multiple billions of dollars annually, according to an estimate by the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC).

“They were among the most powerful and profitable casino and scam operators in the region,” said Jeremy Douglas, regional representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific for UNODC, “and were perceived as untouchable.”

The scam operations, however, led to growing outrage among hundreds of thousands of Chinese victims bilked of their money as well as among the families of trafficked workers. China was finally forced to move against its associates as the theft and trafficking became a domestic political issue, officials and analysts said. China’s Anti-Fraud Center in late May said police intercepted $157 billion in funds related to scams since 2021. Many more cases have gone unresolved.

Spokesmen for Myanmar’s State Administration Council and the Myanmar military did not respond to requests for comment. China’s Foreign Ministry, Yunnan’s provincial government and Lincang’s city government also did not respond to requests for comment. The Post emailed the companies run by the Kokang families, including the Lius’ Fully Light Group, Warner International, the Gobo East subsidiary and the Weis’ Hanley Group, at addresses still listed on their websites, and did not receive any response.

Despite Beijing’s ongoing crackdown, these criminal networks have proved difficult to eradicate. Subsidiaries and operations linked to the Kokang families remain intact, according to an analysis of their cryptocurrency wallets by the firm Chainalysis and in-person visits to the families’ offices in Yangon, Myanmar’s commercial capital. Scam operations run by rival groups continue to grow in other parts of Myanmar and Southeast Asia.

“The Kokang families were engines for the Chinese-Myanmar economic relationship. Their economic sway came from [illicit businesses] but also from this massive web of relationships that they built with economic and political elites all across China,” said Jason Tower, director of the Myanmar program at the U.S. Institute of Peace.

China, he added, has helped create “a Frankenstein monster that it now can’t control.”

Vast casinos

Far from the Myanmar heartland, Kokang has long been synonymous with vice — from heroin and methamphetamine production to gambling dens, all of which thrived under warlord Peng Jiasheng and his Myanmar National Democratic Alliance (MNDAA) rebel army.

In 2009, the Myanmar military moved against the MNDAA, defeating the group after co-opting some of Peng’s top men. For bringing the territory under central control, the commander who led the operation — Min Aung Hlaing — was handpicked to lead the military two years later. And the MNDAA leaders who flipped — members of the Bai, Wei and Liu clans — were rewarded with control over the region and its underground economy, analysts said. They became leaders of the Kokang Border Guard Force, a subdivision of the Myanmar military, and of the Kokang regional administration.

The clans controlled every aspect of life in Kokang, becoming lawmakers, militia heads, local administrators and powerful business executives. They “got involved in all kinds of illegal businesses that were already there, and built up much more,” said Richard Horsey, the International Crisis Group’s senior adviser for Myanmar.

At the same time, their ethnic Chinese identity strengthened their position as Xi encouraged regional investment, and as ties between the Myanmar junta and the Chinese Communist Party deepened.

Local authorities in Yunnan worked with the families on investment opportunities such as an expanded port and two cross-border economic zones, according to official Chinese statements. In 2017, as Xi gathered foreign leaders in Beijing for the first Belt and Road Forum, China’s state broadcaster featured the newly expanded Qingshuihe port connecting Yunnan to Kokang as a model project. Soon afterward, China allocated $6 million in central government subsidies to the border trade zone. China’s Finance Ministry organized funding from the Asian Development Bank, which eventually approved $250 million in loans for roads and other infrastructure after Chinese officials visited the border in April 2018.

Qingshuihe port connecting

Yunnan, China, to

Kokang, Myanmar

Qingshuihe port connecting

Yunnan, China, to

Kokang, Myanmar

Qingshuihe port connecting Yunnan, China, to Kokang, Myanmar

Qingshuihe port connecting Yunnan, China, to Kokang, Myanmar

It was an extension of Beijing’s overall approach in restive borderlands: development as a path to stability.

“China’s chief objective for Kokang is to secure the border, and to do that you have to help the other side resolve economic and livelihood problems,” said Liu Yun, a fellow at Taihe Institute, a Chinese think tank in Beijing.

A spokesperson for the Asian Development Bank said the Yunnan-Lincang project was “designed to improve the economic growth potential and the standard of living” of residents in those parts of China and “surrounding areas,” and that the project was developed “in compliance with ADB policies and procedures.”

The families grew their holdings into diversified conglomerates. The Liu family’s Fully Light Group, in particular, became involved in every lucrative industry in Myanmar, including real estate, hotels, gems, agriculture, cigarettes, pesticides and more, and opened subsidiaries in China and Cambodia, corporate records show.

But at the heart of the Kokang empire were casinos, underground banking and money laundering, according to U.N. officials and U.S. diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks.

High-rollers and ordinary Chinese gamblers flocked to the porous border between Yunnan and Kokang. Newly built mega-casinos in the Kokang capital, Laukkaing, opened 24 hours a day. The Kokang clans planned to build an airport and pitched themselves as a Macao-like destination for foreign tourists.

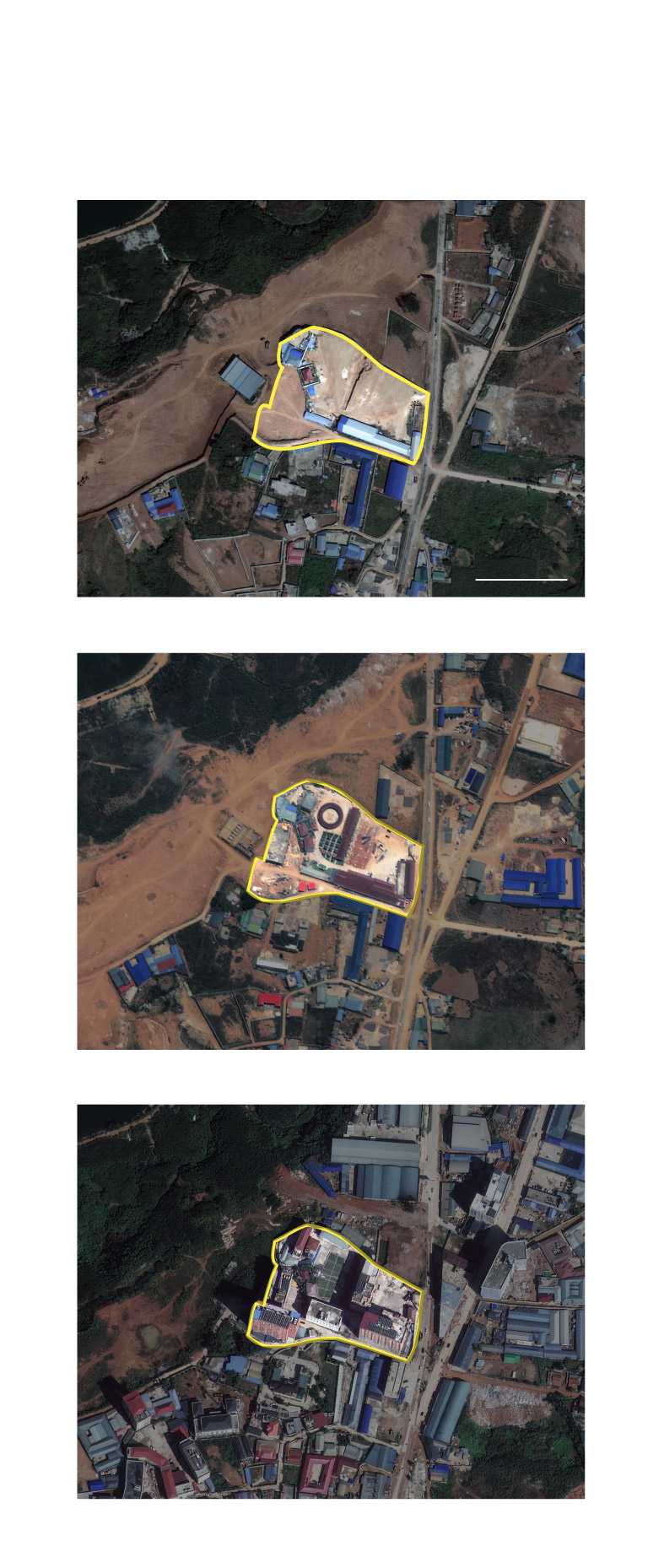

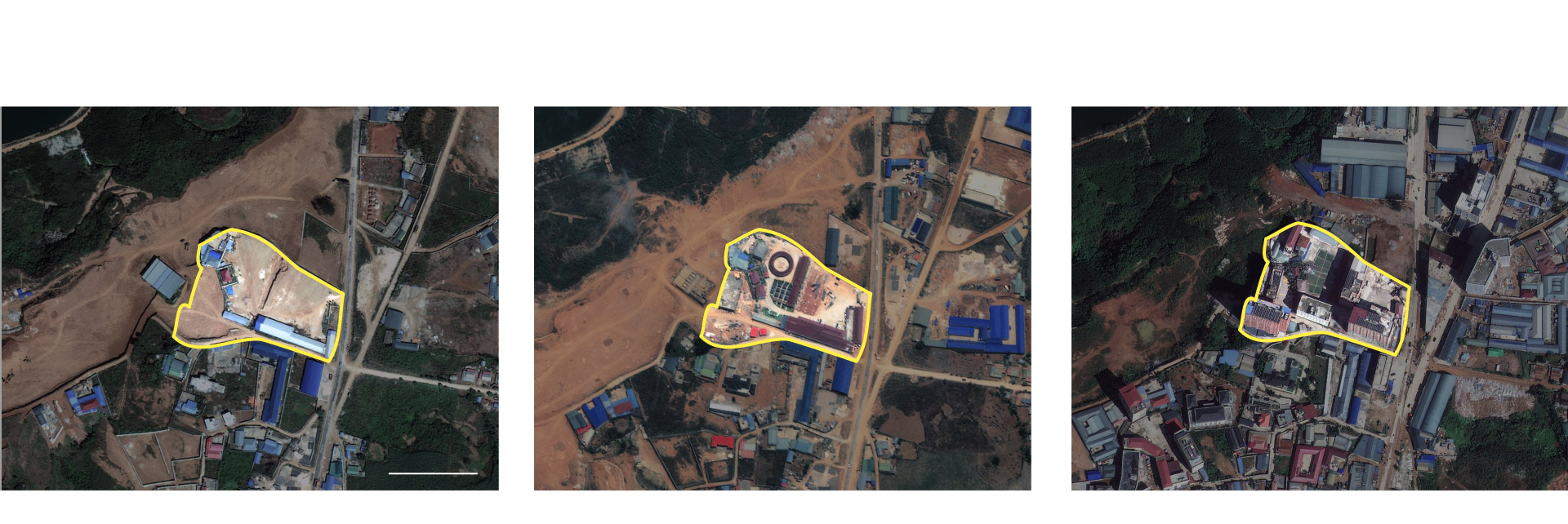

Behind the vast casino floors, a more sinister industry started to grow. Chinese court documents show that from at least 2018 “criminal syndicates” were smuggling people into the Crouching Tiger Villa, a banquet hall and hotel, and forcing them to work as scammers. The compound is owned by the Ming family, henchmen for the Bai clan, according to Chinese state media and a person who worked at the villa.

Within a few years Crouching

Tiger Villa had ballooned

into a massive scam compound

Before villa was

constructed

Villa constructed, initial

scam centers built

Expanded scam center

buildings after raid

Source: Satellite image ©2024 Maxar Technologies

Within a few years Crouching

Tiger Villa had ballooned into

a massive scam compound

Before villa was

constructed

Villa constructed, initial

scam centers built

Expanded scam center

buildings after raid

Source: Satellite image ©2024 Maxar Technologies

Within a few years Crouching Tiger Villa had

ballooned into a massive scam compound

Before villa was

constructed

Villa constructed, initial

scam centers built

Expanded scam center

buildings after raid

Source: Satellite image ©2024 Maxar Technologies

Within a few years Crouching Tiger Villa had ballooned into a massive scam compound

Expanded scam center

buildings after raid

Before villa was

constructed

Villa constructed, initial

scam centers built

Source: Satellite image ©2024 Maxar Technologies

Border closures that followed the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic shut off the cash flow to the casinos, accelerating a shift to this new scam economy. But it was the 2021 military coup in Myanmar that supercharged Kokang. Min Aung Hlaing turned to the families for an economic and political lifeline, including large tax payments, as Western sanctions mounted against his government. The families donated lavishly to the general’s pet projects, such as building marble Buddha statues and pagodas, and leveraged their ties to China to keep bilateral trade and infrastructure projects going, according to the Kokang administration’s social media posts and Myanmar state media. Clan patriarchs became among the most decorated citizens of Myanmar, honored with a number of awards, and represented Myanmar at major regional summits.

The families “felt they could do anything,” said Horsey at the ICG.

The scammers — from just across the border in China and as far away as Malaysia — were effectively imprisoned in Kokang’s purpose-built compounds. Sitting at computer screens in large dormlike rooms that resembled call centers, they were trained to cultivate people who could be drained of their savings.

Scammers were to talk up business trips and ties with elderly relatives to “establish an image of responsibility, kindness and respect” while sprinkling in “light discussion” of an “investment” opportunity, according to notes found inside the Crouching Tiger Villa and posted on Douyin. In courting romance, they were to assess if the mark preferred talking about their day or just sex, a scammer said.

Many of the compounds for running scam operations were hosted in the same hotels and casino complexes long established by the clans. Others were purpose built, but had telltale signs like barred windows, high walls and even Myanmar military snipers on the rooftops, witnesses said.

A handyman, hired to build soundproof phone booths within a scam compound in a hotel owned by the Liu family, said he was interrupted by screams as he worked. He said he saw a supervisor beating three men, their hands tied behind their back, with lead pipes. A Taiwanese woman, who was trafficked into Laukkaing, told The Post she was waterboarded when she tried to escape. A Chinese man, who was forcibly brought into Kokang by knife-wielding men after responding to an acting job online in China, said he saw others in his compound chained and beaten. At one point, four people were shot when they fought back during beatings and tried to seize guns from the guards, he added in an interview.

The Crouching Tiger Villa was among the most brutally run compounds, witnesses said. There, caged lions, tigers and bears were used to threaten workers who stepped out of line, according to a person who led a team of workers there.

Clans also hired foreign security personnel to protect their interests. Alex Klisevits, a former Estonian navy officer, was among a team of 11 who arrived in Kokang after responding to a job ad seeking close protection officers for a “Chinese businessman.” Klisevits said he was smuggled in and soon realized he was not free to leave. The first day on the job, Klisevits said he saw a chained man beaten unconscious.

“When I saw how they punished people … I thought, ‘where the hell am I?’” Klisevits said.

By 2023, Beijing was coming under growing domestic and international pressure to act against these operations. The United Nations estimated in a report last year that more than 120,000 people were being forced to work in Myanmar. Rescue groups said this was a conservative estimate.

Trafficked people working in scam centers in the region have been recorded from at least 35 countries, including the United States, Uganda and Brazil, according to the State Department’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, but most are from China.

The scamming became such a public matter in China that it was fictionalized in one of the country’s highest grossing movies last year. The film, “No More Bets,” follows a Chinese software engineer trafficked into a place that closely resembled northern Myanmar, where he was forced to work as a scammer.

Signs of official Chinese concern burst into the open in August when the Chinese ambassador warned Myanmar authorities to “eradicate the cancer of gambling and scams” that was “deeply loathed by the Chinese people.”

Compounds in Laos and Cambodia were raided by local police, accompanied by officers from China. In Myanmar, the Kokang clans vowed to conduct their own crackdown, claiming they would never tolerate such activities in their region. The raids and arrests that followed were performative, U.N. officials and researchers said.

“China did send lots of signals to the Myanmar military beforehand,” said Xu Peng, a PhD candidate at the SOAS University of London who has extensively researched the Myanmar-China borderlands. “[Min Aung Hlaing] either did not understand these signals, or had no willingness to crack down, because of his personal history. Kokang was what he perceived as the beginning of his rise.”

Word began to reach workers that China wanted them home and escape attempts rose. At the Crouching Tiger Villa on Oct. 20, guards opened fire when over 100 people tried to leave. The Post could not verify how many died, but four undercover Chinese police officers were among those killed, according to accounts from Kokang residents and Sammy Chen, an independent consultant who worked with dozens of families and authorities in China and Thailand to extract people from scam compounds.

Confession videos featuring Wei Qingtao and two others — individuals from the Liu family and the Ming family — began to appear on Chinese media. Their video statements were almost identical. Two of the Mings were arrested in Myanmar by local police and handed over to China. The patriarch, a former military-allied lawmaker, Ming Xuechang, died during a Myanmar police raid from a “self-inflicted gunshot wound from his own pistol,” according to Myanmar state television. In December, China issued arrest warrants for 10 more heads of the Bai, Wei and Liu families, and their children.

Emboldened by Beijing’s crackdown, the MNDAA formed an alliance with two other ethnic armed groups and attacked junta positions nationwide. The MNDAA’s slogan was designed to appeal to Beijing: “wipe out the scammers, rescue our compatriots.”

On Jan. 6, Laukkaing, the capital of Kokang, fell to the MNDAA, returning full control of the region to the rebel group for the first time in 15 years. The MNDAA did not respond to requests for comment.

It was the Myanmar military’s most significant loss of territory since the country’s independence. And it would have been impossible, analysts say, without the explicit or tacit support of China. The MNDAA has since worked with China to repatriate foreigners from Kokang, according to diplomats involved. Since last July, 49,000 scam workers have been returned home to China, according to the Ministry of Public Security.

Several senior clan figures are now facing fraud and potentially other charges in China, officials said, carrying a maximum sentence of life in prison, but many have slipped away.

The Post provided verified addresses of cryptocurrency wallets linked to the Lius’ Fully Light Group and its subsidiaries, including an online casino operator, Warner International, to Chainalysis, a blockchain analysis firm. Chainalysis found that these businesses continued to move millions around through intermediary wallets as recently as April.

“These crime organizations are too complex to be taken down in a single action,” said Xue Yin Peh, a senior intelligence analyst at Chainalysis.

The cryptocurrency of choice, said Douglas of the UNODC, is Tether, the world’s largest stablecoin whose value is pegged to the dollar. Fully Light subsidiaries such as its Gobo East casino in Cambodia are still trading in Tether, Douglas said.

“Key parts of the corporate empire are still up and running.” he added.

Cyberscam operations, many operated by other ethnic Chinese gangs, continue to expand into other parts of world — especially Cambodia and Laos, but also as far away as Dubai, South Africa and Georgia, according to the U.N. researchers and anti-trafficking rescue groups.

“What began as a regional crime threat in Southeast Asia has become a global human trafficking crisis, with millions of victims, both in the cyberscam centers and as targets,” Jürgen Stock, the Interpol secretary general, said in March.

Beijing’s crackdown has nonetheless had at least one major effect on the scam industry. Operations run by ethnic Chinese gangs, researchers and rescuers say, are now targeting English speakers, including Americans, over Chinese victims to avoid Beijing’s wrath.

“They’re moving out of Kokang to areas that are less vulnerable to Chinese law enforcement expansionism,” said Jacob Sims, formerly of International Justice Mission, an anti-trafficking NGO, and now a visiting expert at USIP.

Even in Kokang, analysts say, illicit businesses and human rights violations are likely to persist — shifting only to take account of Chinese domestic sensitivities. The MNDAA in late April posted a video showing the public trial of some of its own fighters, three of whom were executed after the hearings for crimes including kidnapping and murder. The European Union condemned the executions, which it said were the “ultimate denial of human dignity.”

“The issue for Beijing [in Kokang] is not the illicit economy, it is illicit activity that targets Chinese nationals,” said Morgan Michaels, a research fellow at the International Institute for Strategic Studies who studies conflict in Myanmar.

The casinos and hotels owned by the Kokang crime families still stand, but have gone dark. Hanley Interstellar, Wei’s club, is deserted. So too is the Crouching Tiger Villa, its walls crumbling and pockmarked with bullet holes, verified videos show.

But some of the exotic animals — a tiger and five bears — survived the conflict. They still roam their cages, depending on rebel soldiers to bring their daily meal of chicken.

Alicia Chen in Taipei, Taiwan and two Myanmar-based reporters contributed to this report.