Song Binbin, who has died, probably aged 77, became a poster girl for the bloody Chinese “Cultural Revolution” when on August 18 1966 she was photographed overlooking an immense rally in Tiananmen Square, pinning a red armband, symbol of the Red Guards, on the arm of the Chinese dictator Mao Zedong.

Two weeks earlier she had taken part in the murder of Bian Zhongyun, deputy principal of the Beijing high school she attended, one of the first – and one of the most notorious – of the murders that inaugurated a decade of slaughter in which between one and two million people were killed.

In 2014, however, Song’s public apology for her involvement in the murder – one of the most high-profile expressions of contrition by a former Red Guard – provoked a mixture of scorn and calls for a national reckoning for the suffering and carnage of 1966-76.

In 2013 China’s leader President Xi Jinping had issued a directive banning discussions of “the party’s past mistakes”, and after news of Song Binbin’s apology spread on the internet, the Chinese State Internet Information Office issued a further directive. “Due to the complicated public opinion situation on the Internet,” it read, “all websites are to cool down on their reporting of Song Binbin’s apology. All such reports have to be removed from the front page, while all interactive groups have to stop their discussion [of it].”

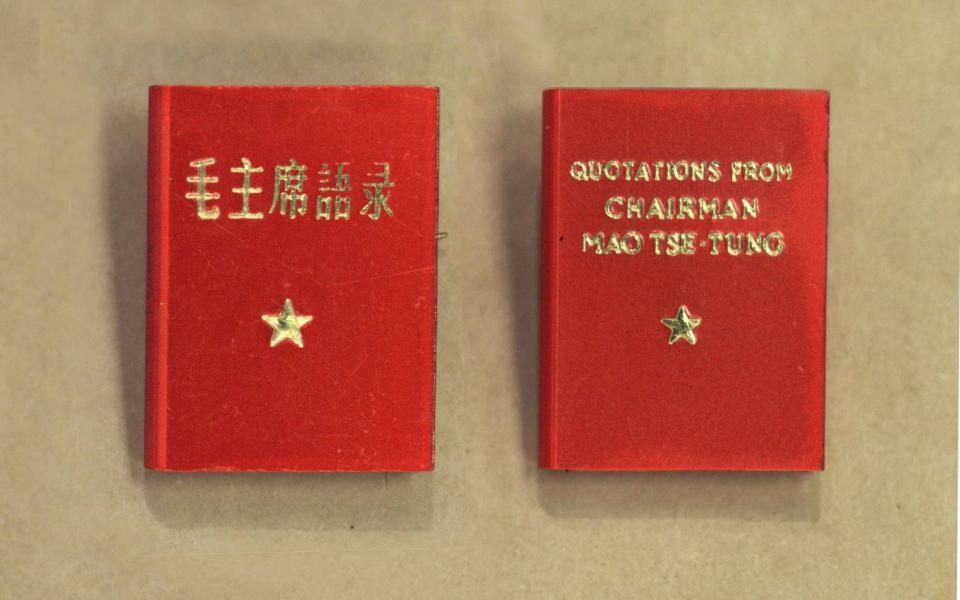

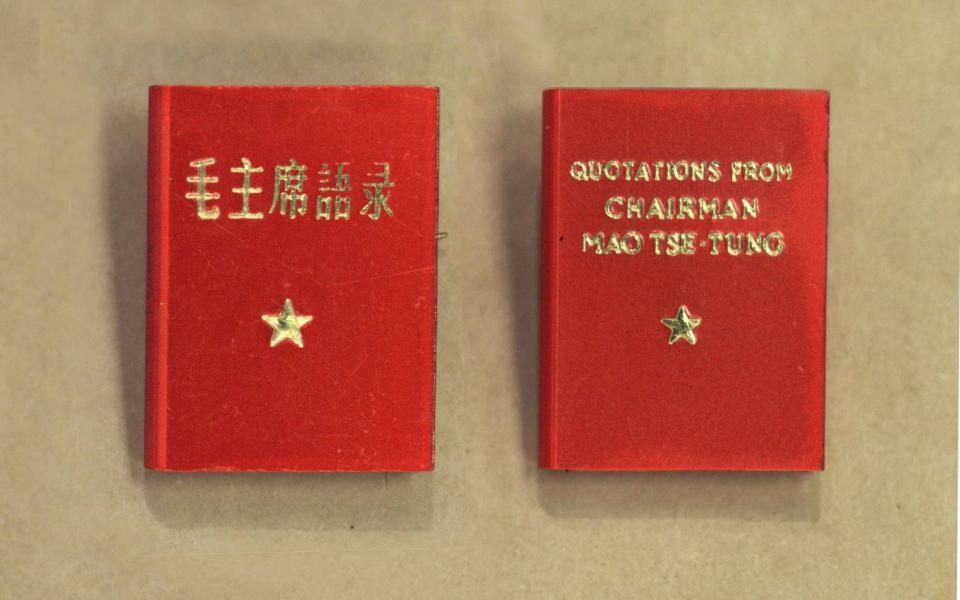

Song had been a student leader of the revolutionary Red Guards at the Girls’ Middle School, attended by the children of the party elite, in 1966 when Mao, in an attempt to regain the initiative after years of failed policies by purging the Communist Party of ‘‘capitalists’’ and “class enemies”, lit the spark for a decade of chaos by urging young people to rise up against their parents and teachers.

Song and another student, Liu Jin, put up the first poster denouncing teachers at the school, before things became violent.

Bian Zhongyun was an obvious target. A 50-year-old mother of four and the daughter of a banker, she was responsible for discipline at the school. Students tested her by asking if they should save a portrait of Chairman Mao if there was an earthquake. Her reply – that they should leave the classroom quickly – condemned her as a counter-revolutionary and proved to be her death sentence.

In her book Red Memory (2023), Tania Branigan described how Red Guards broke in to Bian’s home, burning her books and leaving behind posters threatening to “rip out your dog heart, lop off your dog head”. At the school she was beaten and humiliated by students in “struggle sessions”, dragged on to a stage in shackles and forced to kneel while they kicked and beat her with iron-banded wooden rifles: “When she fell they hauled her up by her hair and began again.”

In her final hours, Bian was beaten with nailed clubs and forced by her tormentors to clean the lavatories and drink from a dirty bucket. When she passed out they loaded her on to a rubbish cart and left her to die in the hot sun, foam dripping from her mouth, while some girls went to buy ice lollies.

After her death her widower, Wang Jingyao, who had been unable to stop the killing, photographed their four young daughters standing next to their mother’s battered corpse. “Mother’s head had a hole in it and she was bleeding profusely,” one recalled. “Her right arm was also bloodied from an injury. The blood ran.”

At the Tiananmen Square rally, Song Binbin was publicly praised by Mao for her role in the atrocity and urged to change her name from Binbin (“genteel”) to Yaowu (“militant”). An article under her new name was subsequently published declaring that “violence is truth”.

Song later claimed, however, that she and other Red Guard leaders had tried to persuade the students not to assault Bian and other staff, and explained that she had been unable to intervene to stop the violence because she was afraid she would be blamed for hindering the “criticising and denouncing efforts”.

So when on January 13 2014 Song Binbin, now 64, visited her old school and, bowing before a bust of Bian, said: “Please let me express my everlasting solicitude and apologies to Teacher Bian”, some of those who had witnessed the events of 1966 – and many who had not – were not disposed to forgive her.

She was accused of lying about her role in the killing. Some witnesses said she personally beat Bian; others claimed that she had abetted or implicitly endorsed the attacks, and had conspicuously failed to help Bian as she lay dying. Bian’s widower denounced her apology as hypocritical.

Hers was not the first public apology for the sins of the Cultural Revolution, but it elicited a much more extreme reaction than previous public apologies. It was not long before the censors moved in.

Song Binbin was born in 1947 (some accounts say 1949), one of seven children of Song Renqiong, a general in the People’s Liberation Army during the time of the founding of the People’s Republic of China and one of the “Eight Elders” of the Chinese Communist Party.

In 1968, like many other party officials at the time, he was purged and expelled from the Communist Party. And as the Cultural Revolution, like many other revolutions, began to devour its own offspring, Song and her mother were placed under house arrest.

In 1969 Song escaped to Inner Mongolia, and in 1972 she enrolled at the Changchun Institute of Geology. After Mao’s death she travelled to the United States, completing a master’s degree in geochemistry at Boston University followed by a doctorate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. After taking US citizenship she worked as an environmental analysis officer for the government of the state of Massachussetts.

Her father, meanwhile, was rehabilitated, becoming vice-chairman of the party’s Central Advisory Committee under Deng Xiaoping and one of Deng’s most ardent supporters during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.

In 2003 Song moved back to China, where she worked for an engineering company.

Song Binbin, probably born 1947, died September 16 2024