There’s no denying faults in technique have slowly crept into the game of the T20-oriented modern batsman

If you’re an Indian cricket follower with a sense of history, the capitulation against Ajaz Patel at the Wankhede Stadium on Sunday might just hurt you a little more.

Ask any Indian batter of the 1980s and they would say playing the likes of Padmakar Shivalkar, Rajinder Goel or Raghuram Bhat on the domestic circuit was way more challenging than squaring up against foreign left-arm spinners.

When Sunil Gavaskar finally got out to Pakistan’s Iqbal Qasim on a minefield in his last Test innings at the Chinnaswamy after scoring 96, it was regarded as an exception that merely underlined the rule of general dominance by the batters.

Over the years, left-arm finger spinners continued to be largely seen as restrictive options and it’s hard to find one from visiting sides winning a Test match on his own on Indian soil. Michael Clarke, with a spell of 6-9 at Wankhede in 2004 came close, but VVS Laxman and Sachin Tendulkar had done enough with two superb half-centuries before that which helped India win.

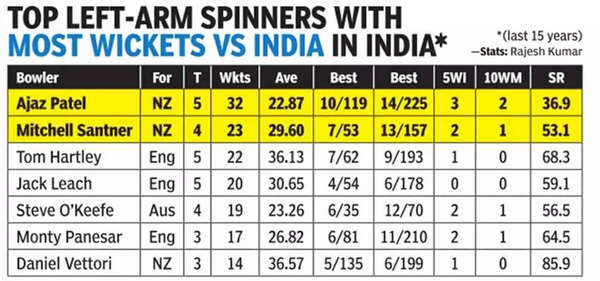

Things, though, have dramatically turned around since the last decade. While India’s last Test series loss at home in 2012 was facilitated by England left-arm spinner Monty Panesar, little-known left-armers like Steve O’Keefe, Tom Hartley or Matthew Kuhnemann have played significant roles in India’s losses in India in the last few years.

But what happened against Ajaz and Mitchell Santner in the series against New Zealand – where they two took 28 of the 60 Indian wickets to fall in the series – topped it all. Superstars like Virat Kohli and Shubman Gill looked like sitting ducks and it always seemed a matter of time before the proverbial death rattle would be heard.

It’s true that the quality of pitches on which Test matches are being played these days are way more conducive to spin than it used to be. In addition to that, the Decision Review System (DRS) has come into play, which has taken front-foot pad play almost out of the window. In this day and age, pad as the first line of defence doesn’t exist anymore and every ball has to be played with the bat, which wasn’t always the case for the earlier generation.

Still, there’s no denying the faults in technique of the modern-day batter that have played a role in this decline in the quality of batsmanship against left-arm spin. Former India batter WV Raman, who also bowled left-arm finger spin, feels that growing up with the T20 mindset is taking its toll on the defence of the young Indian batter.

“It’s basically two things. While the new-age batter more often than not plays with hard hands, the bat, too, doesn’t come down straight. If the bat comes straight and the ball turns a little too much, then there is always the chance of missing the outside-edge. But when the bat is coming that wee bit across the line, the outside-edge always becomes more vulnerable,” Raman told TOI.

There was a notable exception in Rahul Dravid, whose bat used to come down from the gully region, but he had the genius to adjust it at the point of contact and found a way to be behind the line of the ball. The hard-hand bit is a product of too much T20s, where every player is looking to hit the ball with ferocity. “Soft hands are a thing of the past and it means the edges carry to the slips more regularly,” Raman said.

Sunil Subramaniam, another prominent left-arm spinner of yesteryears and one of R Ashwin’s early mentors, feels the tendency to play beside the line and jabbing at the ball is making the modern-day batter vulnerable against left-arm spin.

“Tendulkar, too, sometimes used to get out to left-arm spin, in fact I got him out thrice in domestic cricket. But Tendulkar used to look for shots over extra-cover because that was one of his favourite scoring areas and sometimes gave catches in that region. But I hardly remember him struggling against the ball turning away playing a defensive shot. This is completely a new phenomenon,” Subramaniam said.

Tendulkar did struggle against Panesar in the 2012 series, but by then he was in the last phase of his career. Subramaniam, who had 285 first-class wickets, explained that GR Viswanath was one player who used to play beside the line against left-arm spin successfully.

“But the beauty of GRV was that he could play late with soft hands, a quality that the current crop is losing. The only player in recent times who had the correct technique to deal with it was Cheteshwar Pujara, but then he is no longer part of the team,” the renowned coach said.

He also added that batters these days don’t play spinners from their hands, thereby trying to read them from the pitch, which becomes difficult on sharp turners.