In America, how you spell your name says a lot about when you were born.

Take “Ashley,” for instance. Ashly, Ashley and Ashleigh each mark distinct eras — not just for the Ashleys of the world, but also for the various spellings themselves.

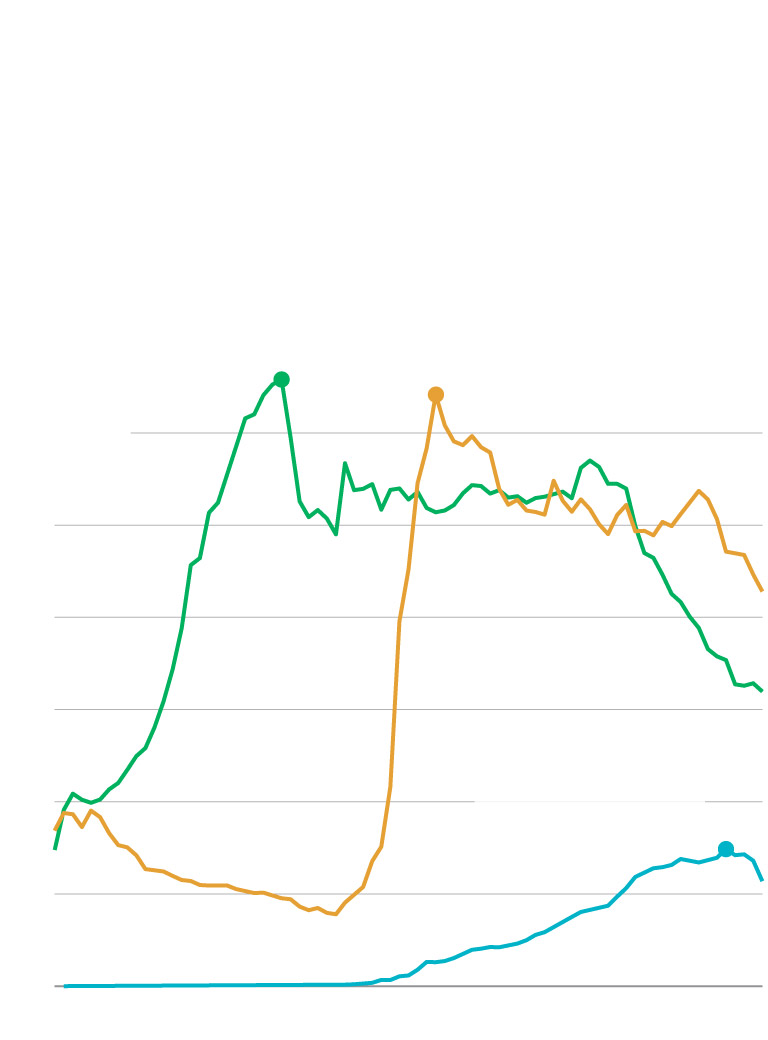

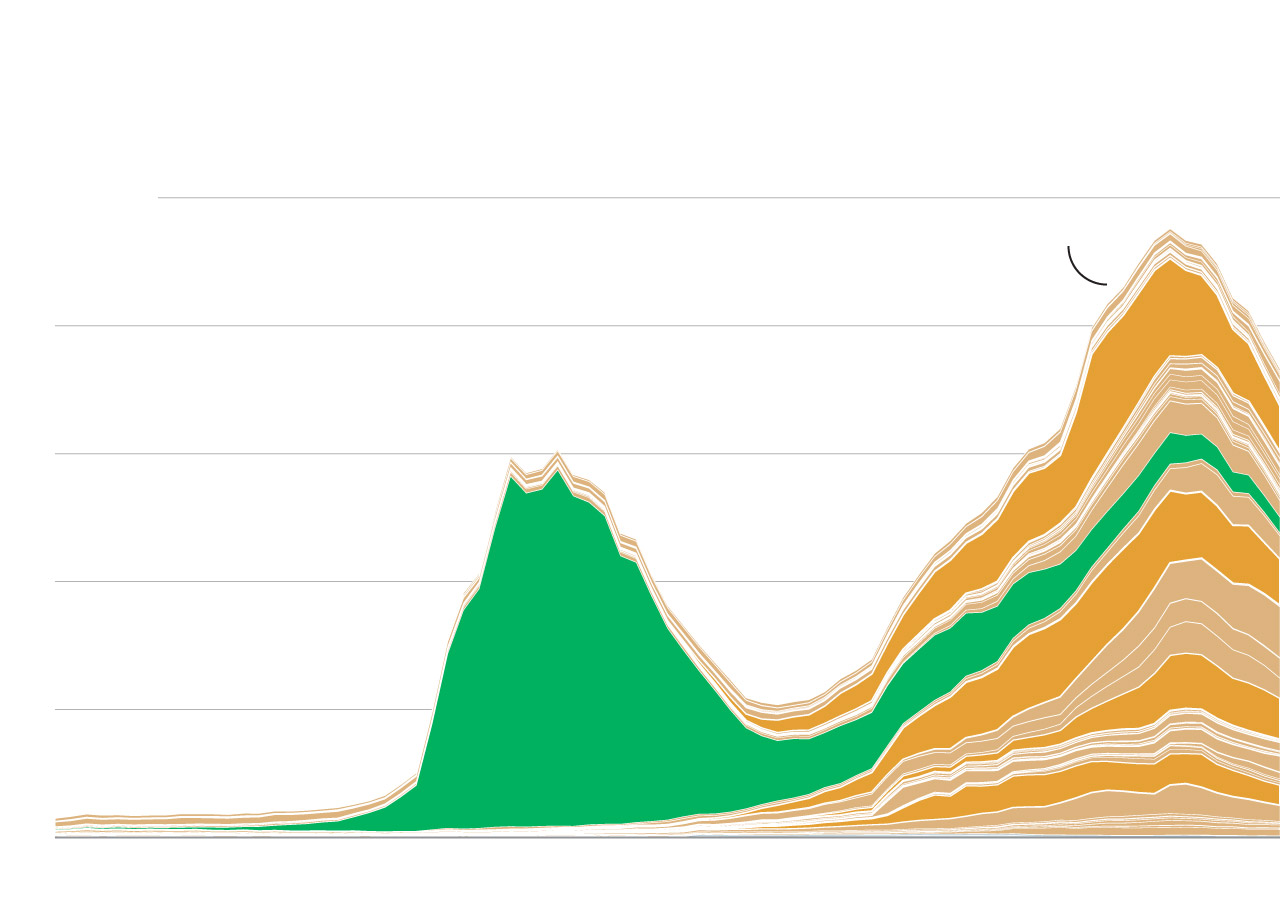

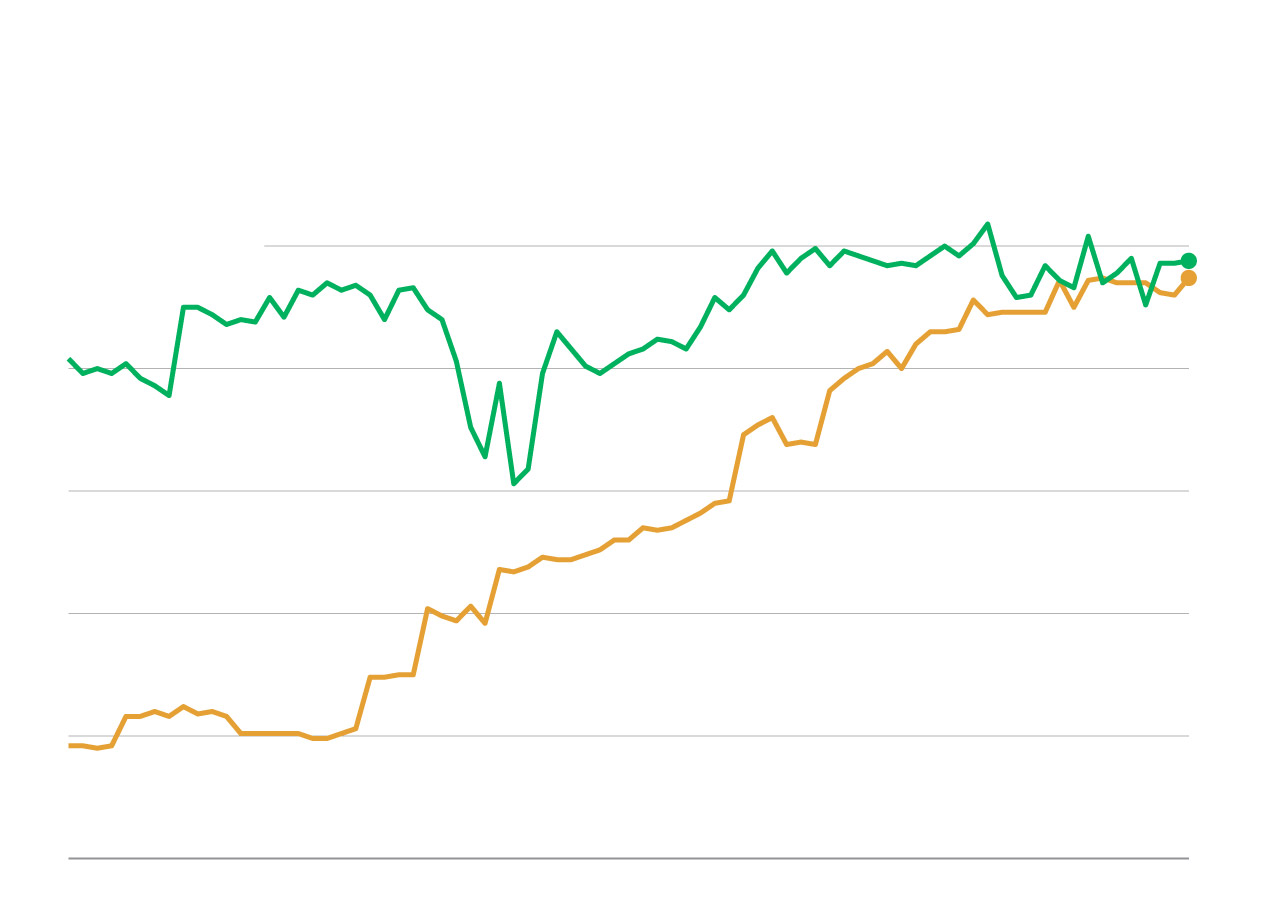

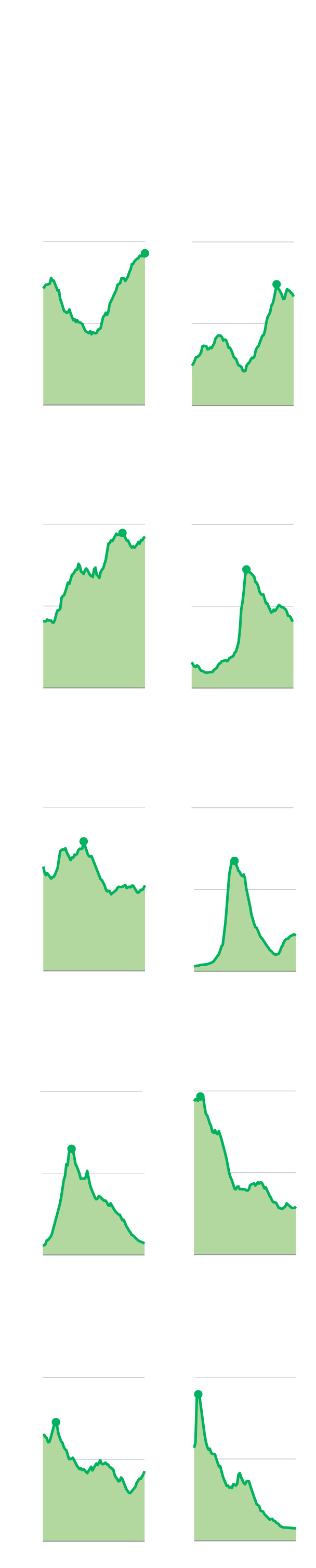

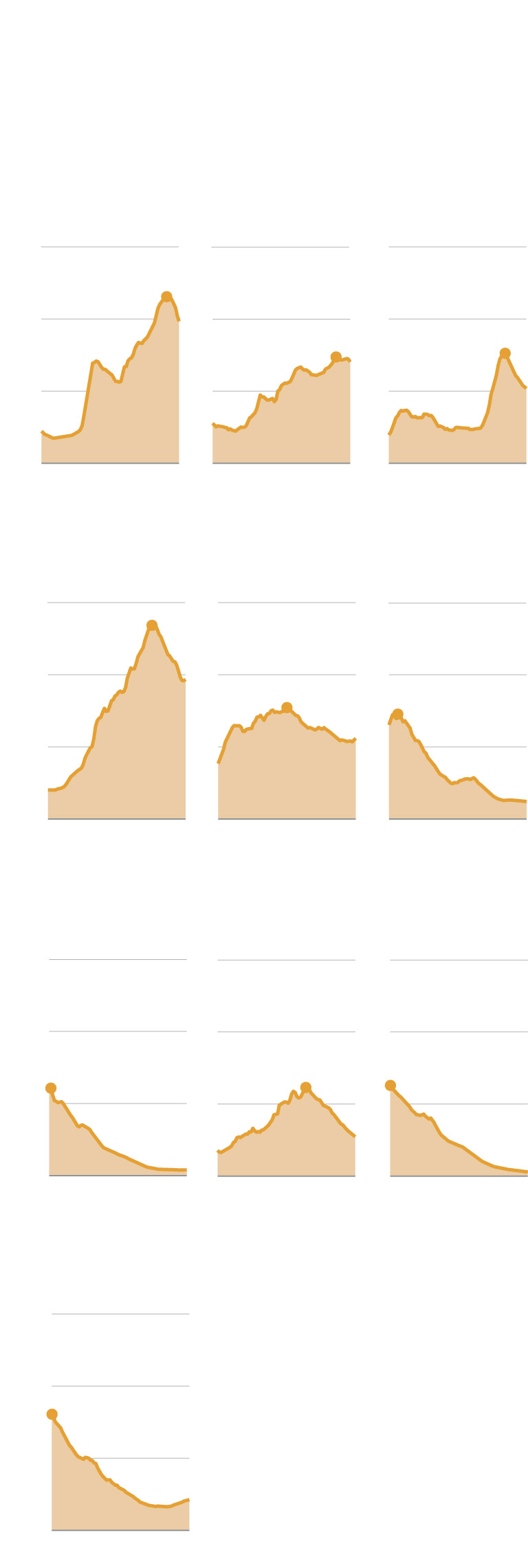

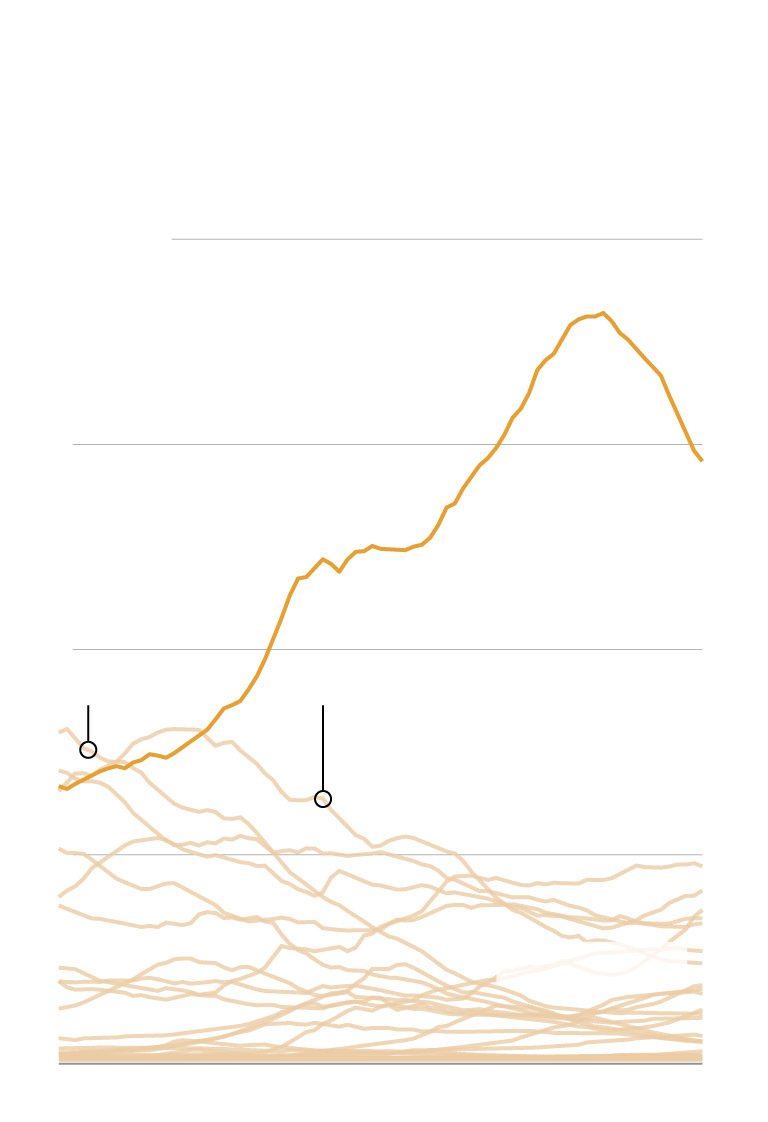

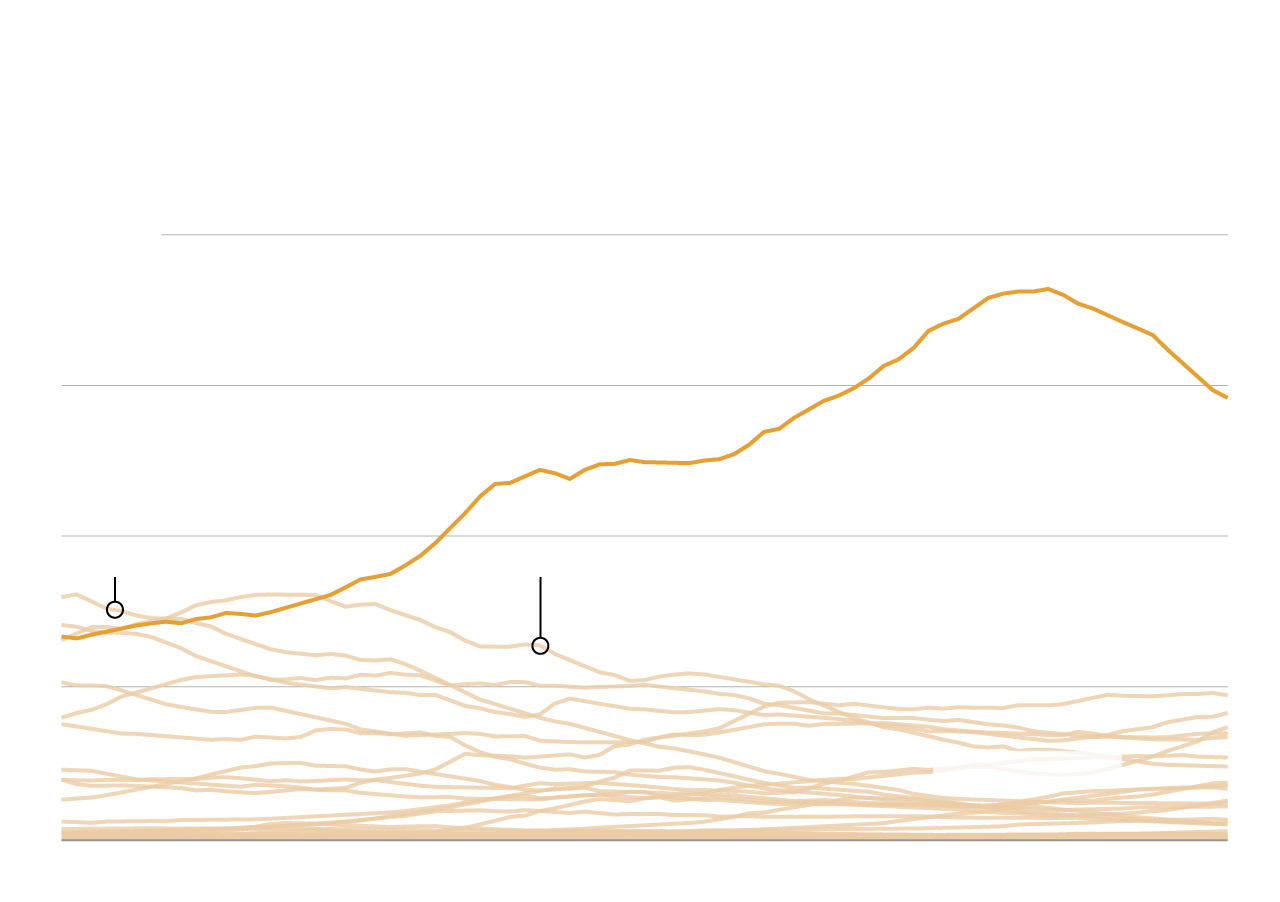

This chart shows the popularity of girls’ names ending in -ly, -ley and -leigh from 1945 to 2023. Names ending in -ly were most popular in 1970, while -ley gained popularity in the 1980s. Names ending in -leigh saw a meaningful rise in the 2010s.

What is it about how we spell a name — specifically, how we choose to spell the end of a name — that makes for a trend? Laura Wattenberg, author of “The Baby Names Wizard” and creator of Namerology.com, a website devoted to the art and science of names, has been examining that question.

You might think trends are defined by specific names. After all, Noah and Olivia have topped the charts year after year, dominating pre-K rosters for more than a decade. With a baby boy due in July, I contacted Wattenberg to find out how I could avoid the trendy baby name trap.

As Wattenberg has watched names rise and fall in popularity over the past 20 years, she said she’s seen the invisible hand of name endings wield surprising influence — especially as Americans have abandoned the use of ancestral names for new family members. While expectant parents want their child’s name to stand out and be memorable, Wattenberg said, they also typically want it to fit within the boundaries of some unacknowledged — but unmistakable! — social convention.

“When you toss away tradition as your source of names, something has to fill that gap and it’s our style sense,” Wattenberg said. “Sound became everything.”

The Social Security Administration maintains an astonishing corpus of American names that could help prove this theory, though Wattenberg hadn’t tackled that task. Indeed, she warned us via email that trying to tease name-ending trends out of the massive SSA database would require “broad statistical categorizations” that force names into unwieldy groupings unlikely to produce neat results.

But here at the Department of Data, we like to respond to such warnings with a hearty “challenge accepted!” And so, with barely two weeks left before my kid’s due date, we find ourselves building bassinets and very wide data sets.

As Wattenberg and I examined the data together, a startling discovery came into focus: Back in the 1970s, singular names grew so popular that they became trends unto themselves. But “it just doesn’t work that way anymore,” Wattenberg said. Nowadays, trends are defined by many different names with similar suffixes.

Consider the awe-inspiring “Jason” curve.

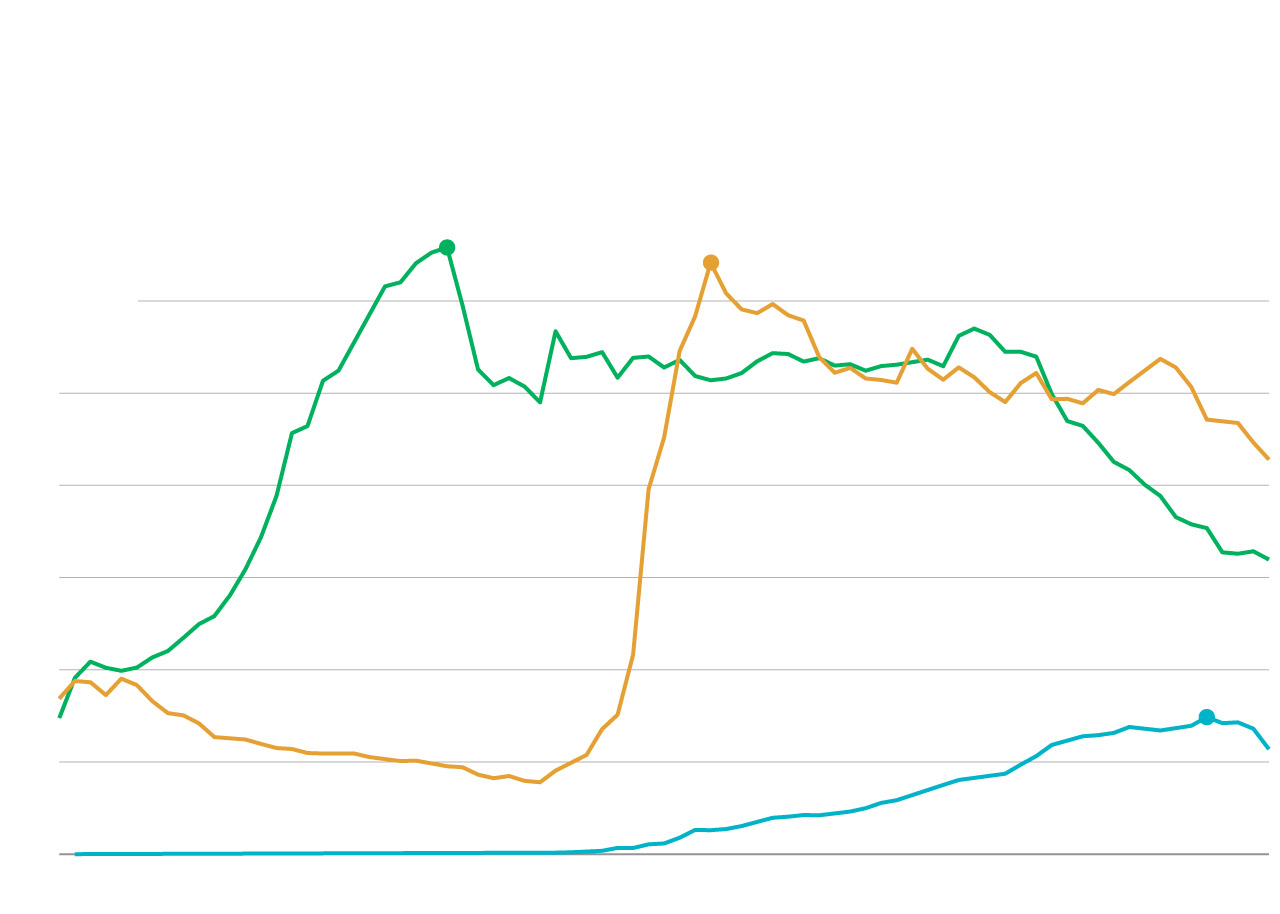

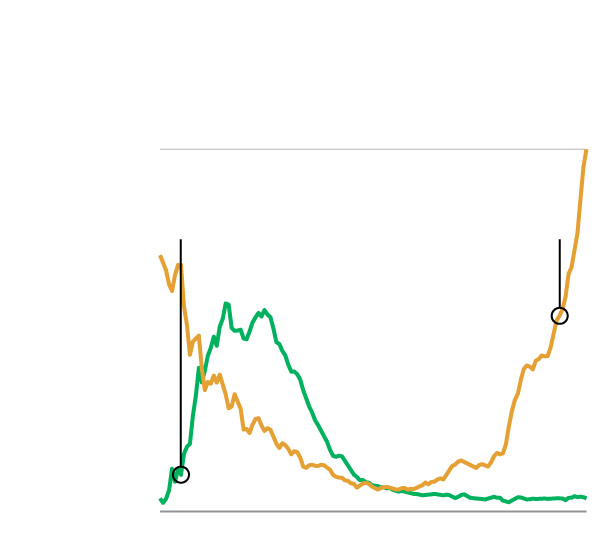

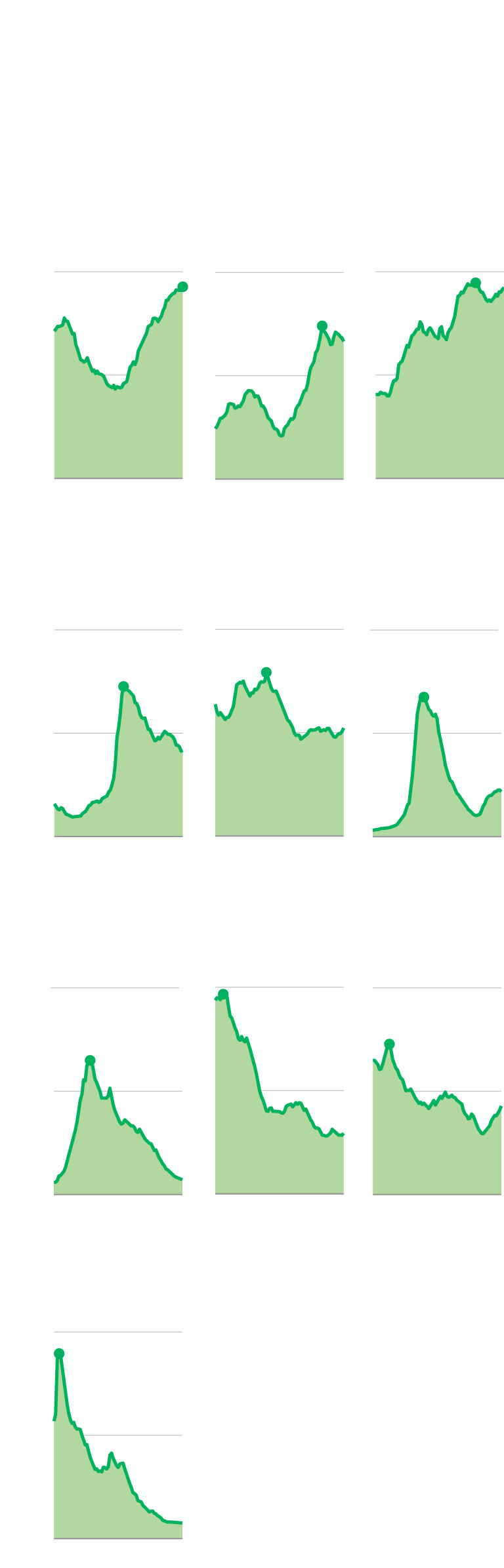

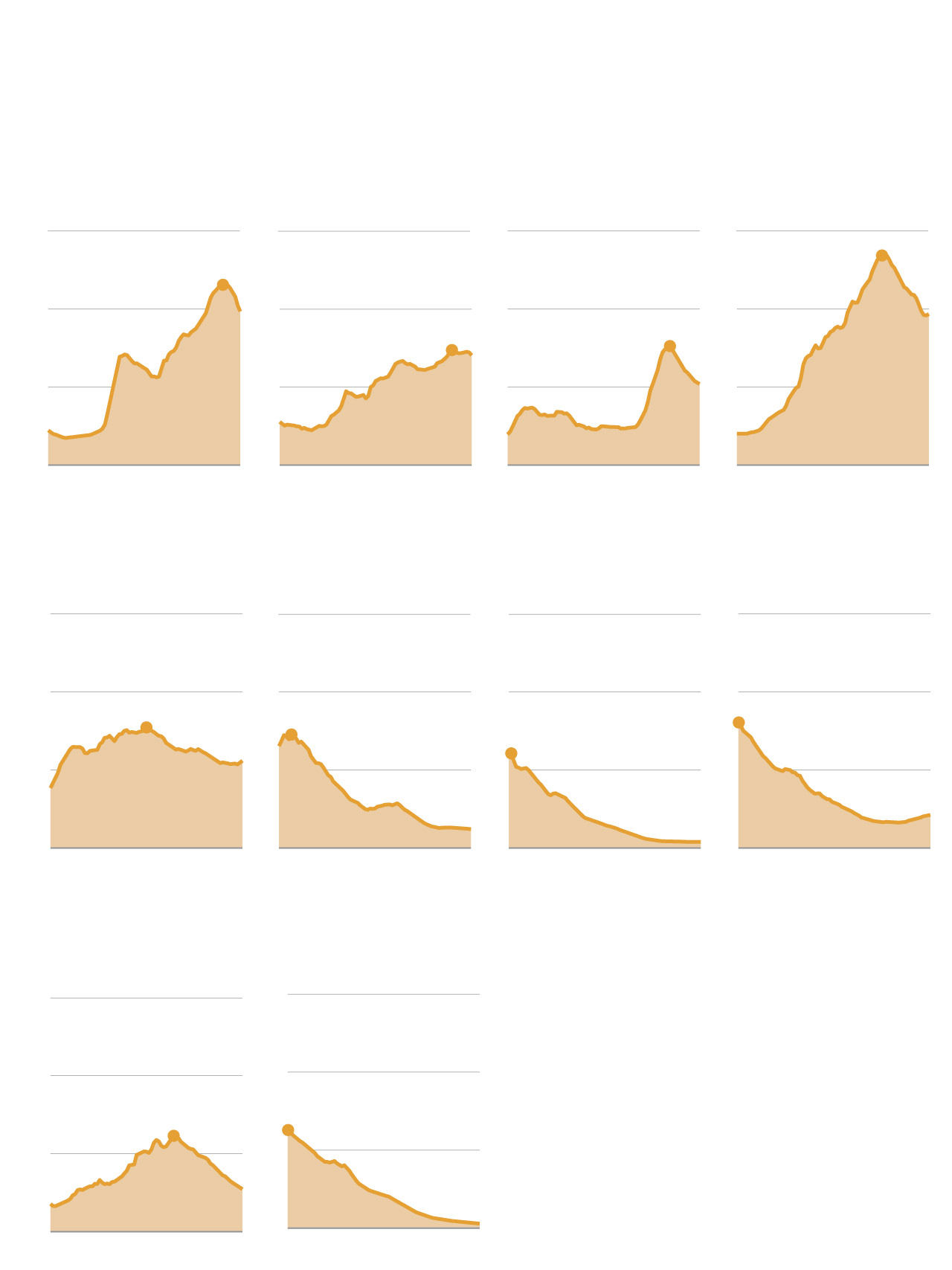

This stacked area chart shows the popularity of boys names that end in “SON”. While in the 1970s and 1980s, Jason was the prevailing name in this category. By the 2010s, that’s eclipsed by other “SON” ending names like Mason, Jackson and Carson.

According to Wattenberg, Jason barely registered in the 1950s when parents often picked a name following family tradition. If your great-grandfather was named Clarence Leroy, odds were a piece of that name would fall intact to you.

Then came the counterculture movements of the 1960s. For the first time, parents began straying from traditional names. With the guardrails of convention removed, people were free to make up their own minds and forge their own paths. And suddenly, by the 1970s, every other kid was named Jason.

Then a funny thing happened: Names started giving way to sounds. Jason begot Mason, Jackson, Grayson, Carson and a whole family of other “-son” names that together make up a major 21st-century trend for baby boys.

To see this phenomenon in your own life, plug your name — or your friends’ names, or your friends’ babies’ names — into our database of name endings.

Wattenberg has a theory about this, too, one she calls her “grand theory” of baby names. It goes like this: In the olden days, Americans shared a monoculture dominated by three broadcast TV networks, no internet and no annual SSA name rankings. (The SSA did not start compiling lists of the most popular baby names in America until 1997.) Hence the frequent reliance on family tradition when a bouncing baby arrived.

Nowadays, she said, people not only have access to unlimited cable channels and the internet, but those innovations have helped usher in a “username creation” mentality — meaning that if someone else has the same name, it’s viewed as taken. So parents tend to tweak their baby’s name just a bit — keeping the “-son,” for example, while swapping the “Ja-” for “Car-.”

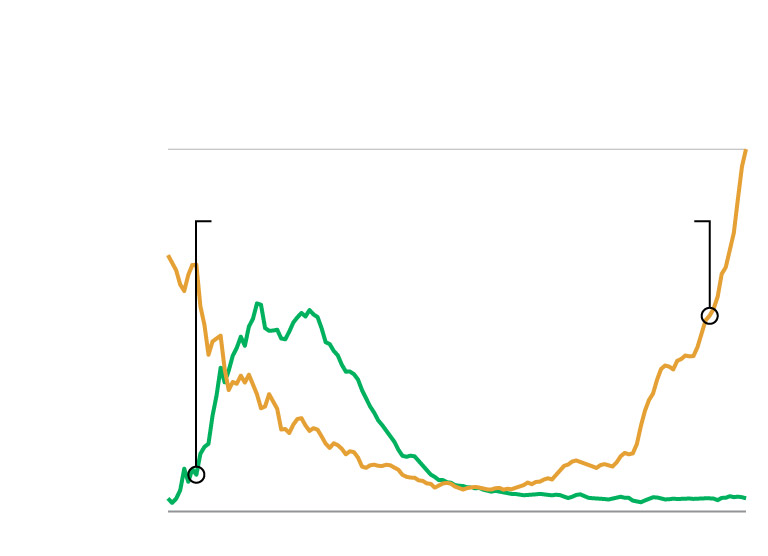

Wattenberg finds “an incredible irony” in this. People think they’re choosing something totally unique, but they do it in a way that winds up moving with the zeitgeist. As a result, names have actually gotten less distinctive over time, with nearly half of all baby names now following identifiable suffix trends — a phenomenon Wattenberg calls “lockstep individualism.”

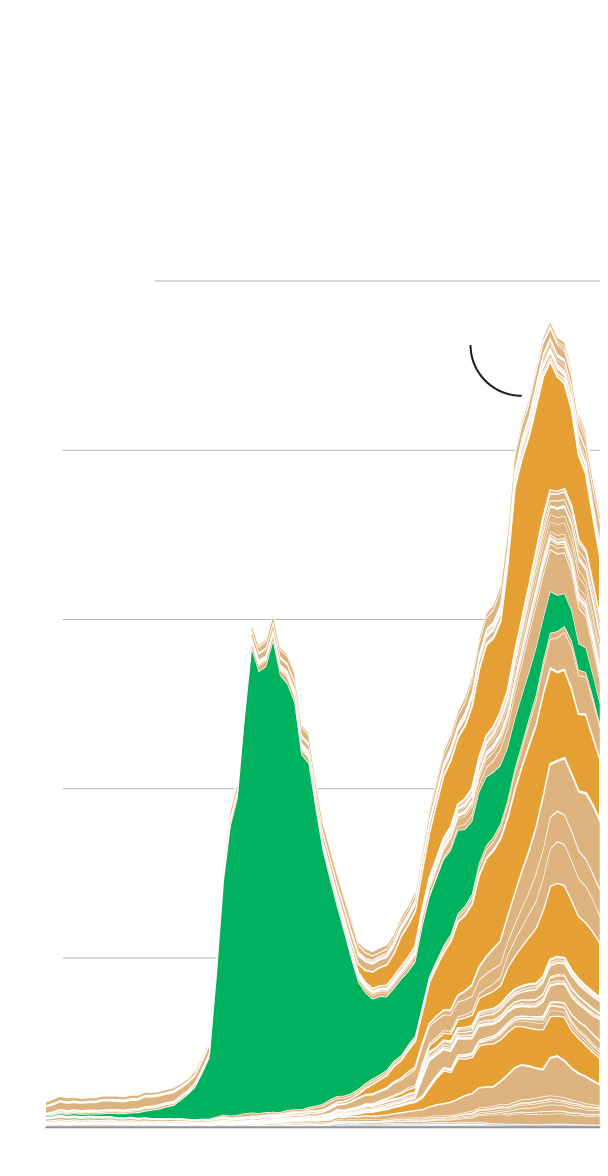

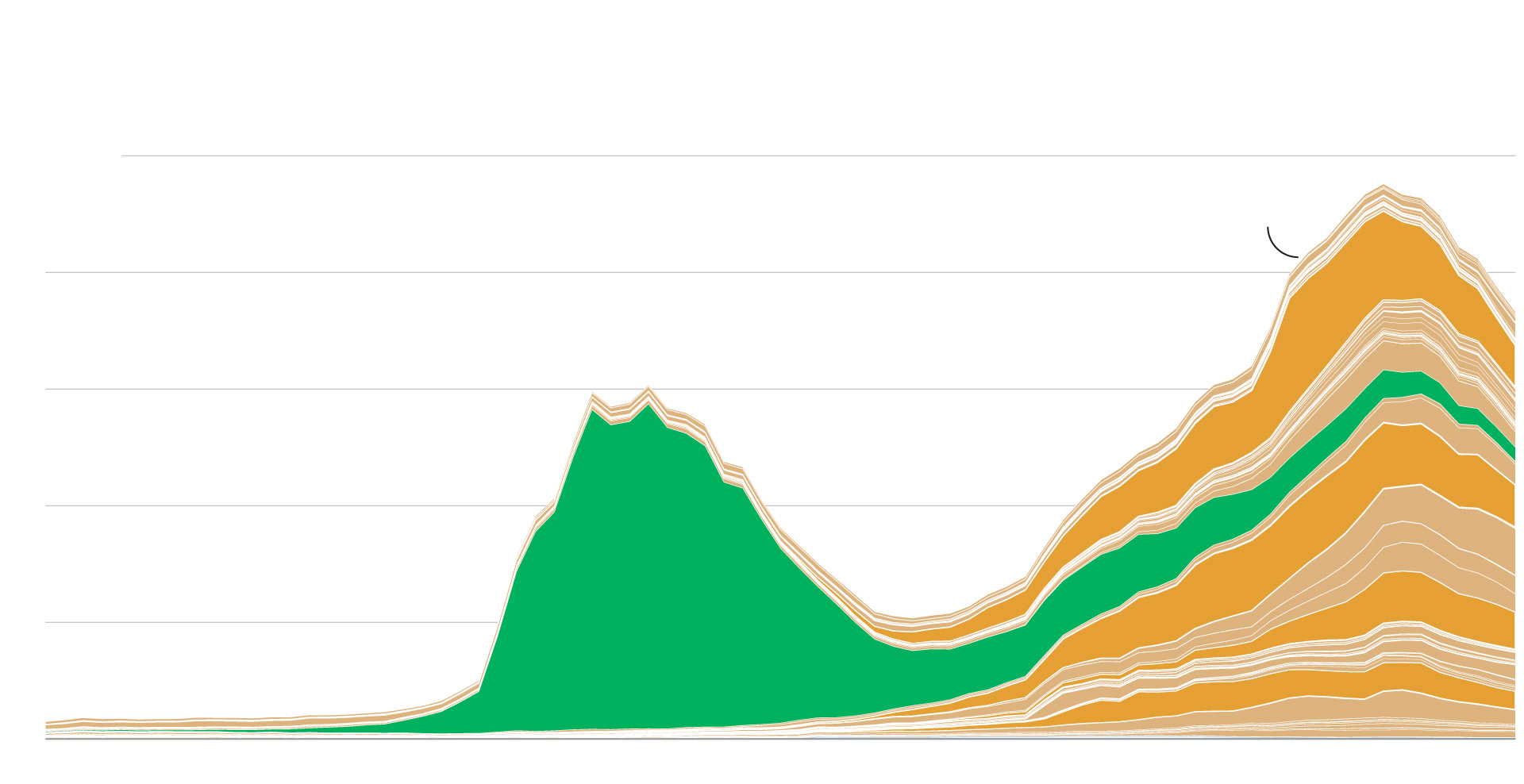

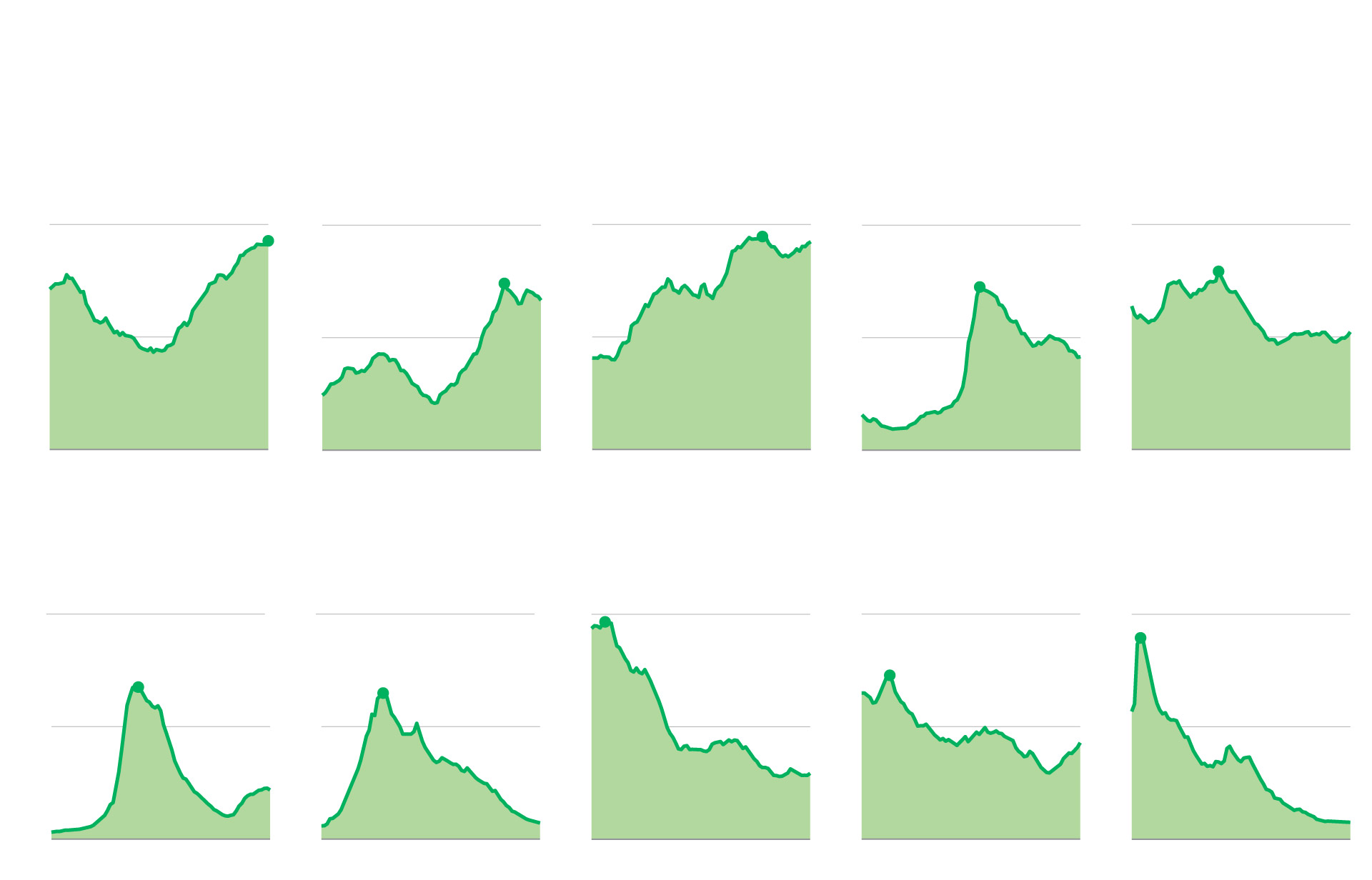

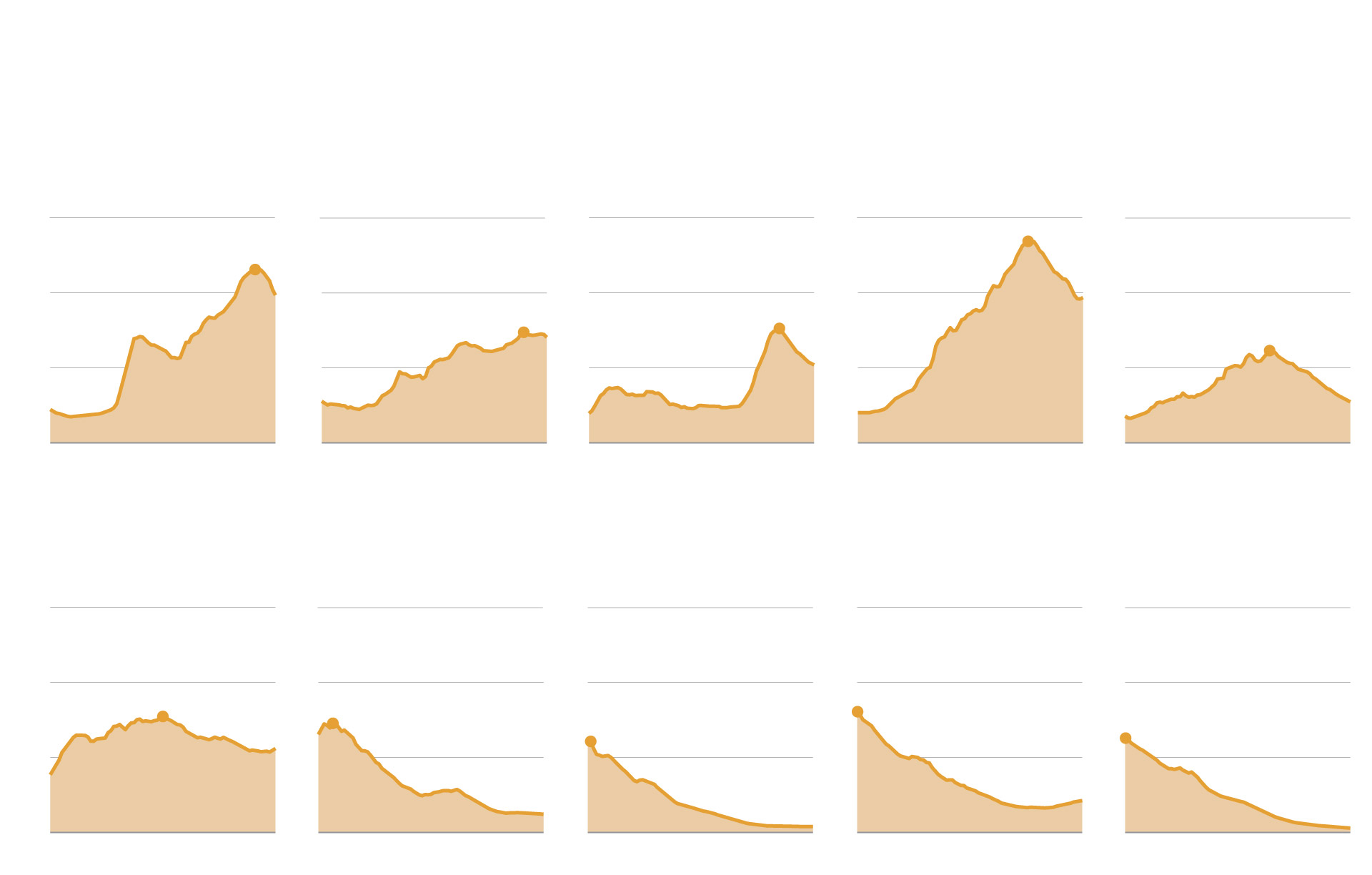

A multiline chart showing the share of common names who have endings in the top 10 endings of the given year. Each line represents boy and girl names. Boy names in particular have gone from more distinct (around 10%) to more similar (nearing 50%) since the 1940s.

How does this happen? Margot Melcon, a playwright based in San Francisco, offers a case study. When Melcon, 38, was pregnant, she and her husband, Jon, wanted their son’s name to stand out.

“We wanted him to be cool,” she laughed on a recent Zoom call. “So how are we going to make our kid sound cool?”

The couple assembled a 20-name list that they kept close to the chest to avoid unsolicited opinions. By the time she went into labor, they had whittled the list down to fewer than eight. But after 40-plus hours of labor and recovery, they looked down at their beautiful baby boy and realized that not one of those options felt right.

With Melcon’s hospital discharge fast approaching, they had three hours to make a decision. Ultimately, they found inspiration in Jon’s family’s bible — an appeal to tradition that Wattenberg said is not uncommon these days.

Inside the cover, the couple found a list of family members who had passed the book down from generation to generation. One name stood out, Melcon said: Cyril.

Cyril was distinctive, she said, but it didn’t quite fit their boy, either. So they tweaked Cyril just a bit to produce Cyrus.

“Cyrus feels very lovely if he’s a poet or a painter,” she said, moving her hands like a conductor or someone pantomiming a swimming squid. “And it would suit him if he was a jock: ‘Cy, pass me the ball!’”

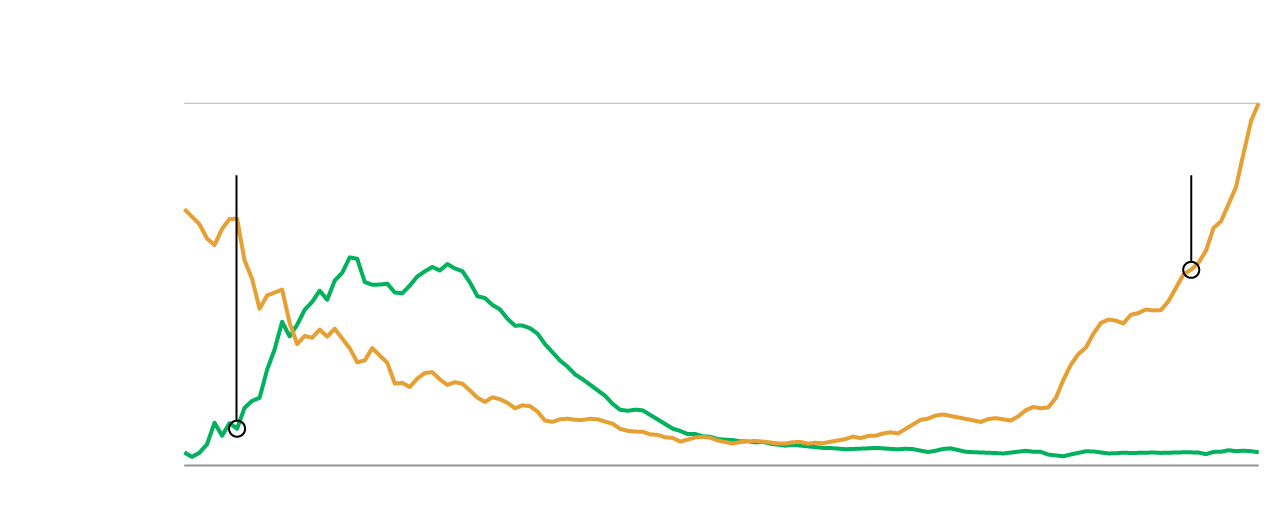

Nothing about Melcon’s experience suggests an effort to follow the herd: The desperate deadline, the mad dash for the family bible, the search for and subsequent discovery of a name that feels uniquely perfect for a tiny new unique human. But when I showed Melcon the data, her “lockstep individualism” was right there in black and white.

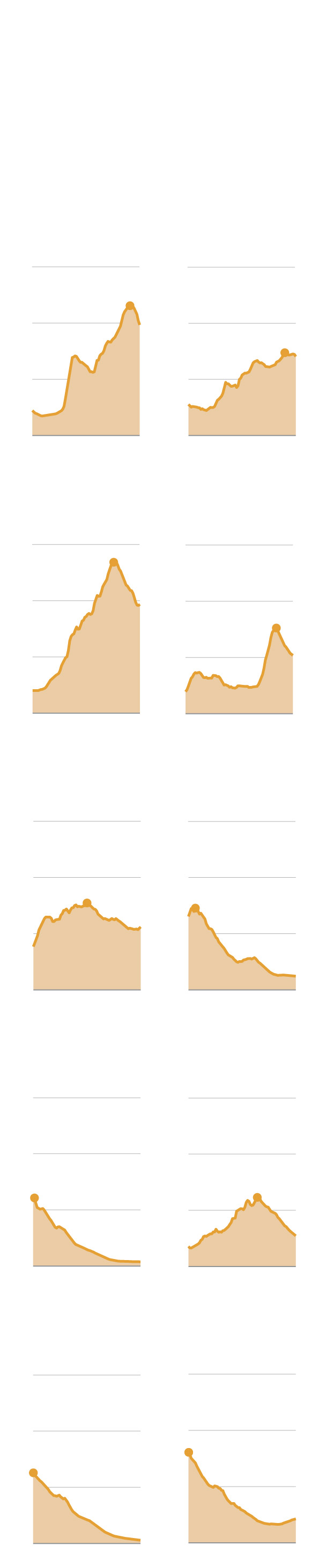

It turns out that Cyril and other “-il” names peaked in the early 1900s; Jon’s ancestor was born in 1887. And “-us” names in boys crested in the 2010s. Little Cyrus was born in 2015.

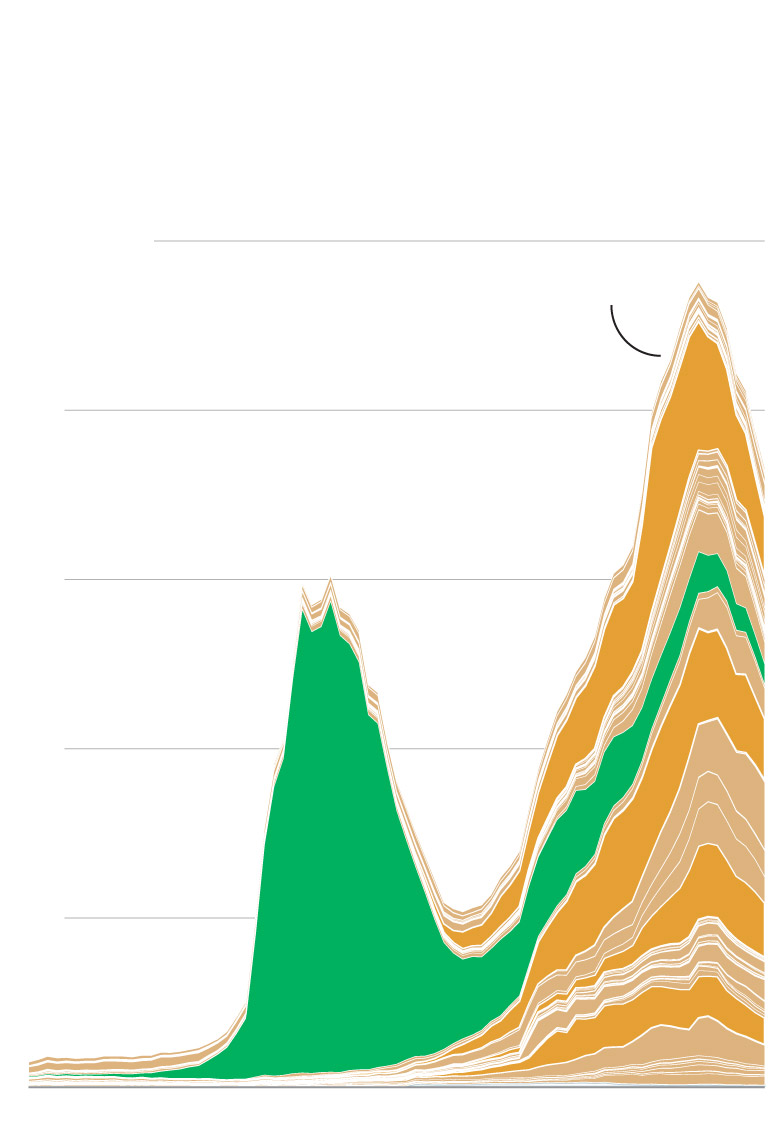

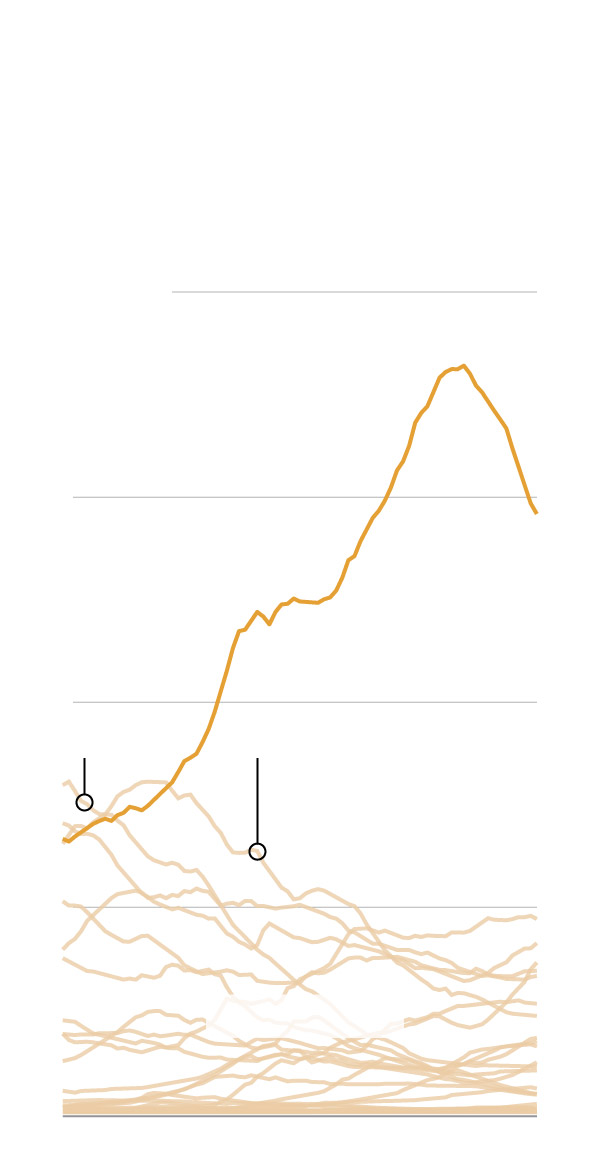

This multiline chart shows the relative popularity over time of the name Cyril and Cyrus. Cyril (and IL ending names) were popular in the late 1800s relative to US ending names. Come the 2010s onwards though, US ending names (and namely Cyrus) is more relatively popular compared to Cyril.

Our Zoom happened to fall on Cyrus’s 9th birthday. When I asked him how he felt about his name, he took a break from his video game to give me a thumbs up. Sometimes his friends call him Cy-Fi — which, admittedly, is pretty cool.

What other trends did we tease out of the SSA data?

For girls: We’re riding a boom in “-ia” names while “-ani/-ari” names also are on the rise, Wattenberg says — perhaps popularized by Kehlani, the singer-songwriter.

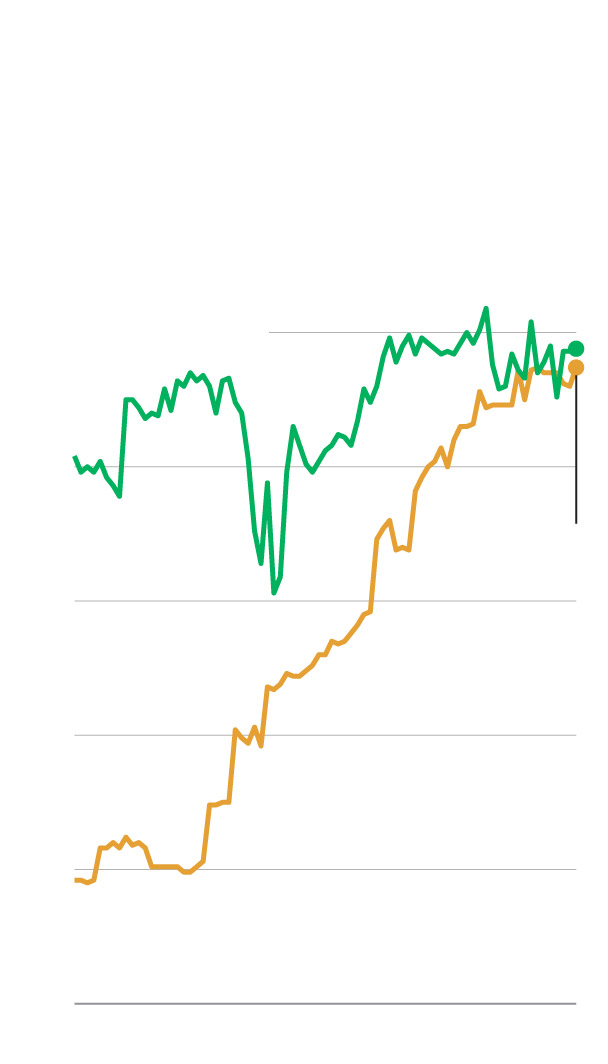

These small multiples show the top two-letter ending names for girls names since 1945. Midcentury names like Catherine and Linda made way for other trends in spellings. Though a majority of girls names end in “A” vowel sounds, spellings still go through eras.

As for boys, the nation’s massive interest in “-on” names appears to have crested.

This small multiple chart shows the rise and fall of different two letter endings of boys names since 1945.

Meanwhile, parents remained fixated on boys’ names that sound like Aiden, though at levels well below the peak Aiden, Jayden and Brayden years of the early 2000s. The first decade of the new century saw the birth of more than half a million boys whose names ended with “-den” — a startling 3 percent of the total.

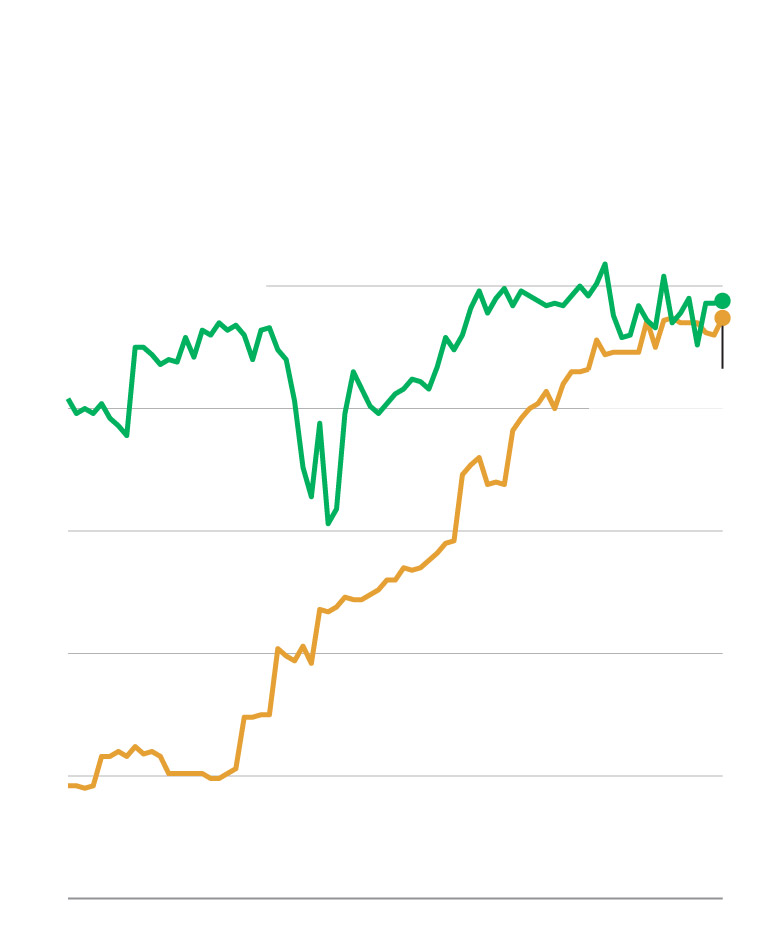

Which brings us to another massive trend that surprised us: When you look at all 26 letters a name could possibly end with, you’ll find that we here in the United States of America have decided that boys’ names should end with “n.”

In 1950, “n” was in a four-way tie with “d,” “y” and “s.” But starting in the mid-1960s, “n” surged ahead. By 2010, nearly 4 in 10 newborn boys were christened with “-n” names.

This chart shows how much the field of letter endings for boys names have changed. Since the 1970s most mens names end in the letter n, consolidating the rest of the letters.

Which brings us back to my boy-to-be naming journey. Much like any expectant parent, my chief desire is for my son to fit in, but also to stand out — a fervent wish for his future that is, of course, outside my control.

Yet like all new parents, I will try.

I won’t reveal our decision, but suffice to say that our son will be joining the 30 percent of newborn boys whose name ends with “n.”

In other words, we picked a name that is perfectly unique.

Hang on there, Data Hive! The Department of Data craves your queries. What are you curious about: Which baby names spark the most regret? Why millennials tend to avoid baby names altogether? Which people names are most often bequeathed to dogs? We’ve already answered those particular questions, it’s true — but surely you have new ones. Just ask!

If your question inspires a column, we’ll send you an official Department of Data button and ID card.

About this story

Lori Montgomery (“–ori” peaked in 1963) and Allison Cho (“–son,” 2008) edited this story. Reuben Fischer-Baum (“–en,” 2008) edited this story’s graphics.

All data comes from the Social Security Administration. In general, we used name counts after 1945 as people born earlier may not have applied for Social Security cards. Names that occur fewer than five times per year are not recorded to protect individual privacy and are excluded from our analysis. Where possible, we calculated a name’s popularity by comparing the number of times it appeared on a Social Security card application against the total number of applications that year.

Andrew Van Dam (“–rew,” 1987) graciously let Daniel Wolfe (“–iel,” 1985) report and write this week’s column. Andrew will be back in the data mines next week.

correction

A previous version of this article misspelled the name of Margot Melcon’s husband, Jon. The article has been corrected.