Daria Korkh made a good show of a stiff upper lip as she prepared to abandon her home.

“We don’t want to, but we’ve got to,” she said bluntly. “The shops and supermarkets are closing. Medical facilities are still open, but it’s only a matter of time before the gas and electricity go.

“The shelling has become more frequent and now there are enemy drones in town. Today the first drone flew in. Everyone knew after they [the Russians] took Avdiivka that this could be expected. It’s not sudden.

Ms Korkh, a practical 39-year-old who has no children but a host of rescue animals (“the kind of pets no one else wants”) is one of thousands of Ukrainians fleeing the strategically vital city of Pokrovsk.

Russian forces have been pushing slowly towards Pokrovsk ever since they captured the strategic city of Avdiivka, 30 miles to the east, in February.

But since Ukraine pulled elite units from Donbas for its incursion into Kursk, the Russia advance has accelerated.

“I’ve never seen such speed [in a Russian advance],” the commander of a Ukrainian aerial reconnaissance unit fighting in the area told The Telegraph this week.

“It is very rapid. And our problem is the same: we don’t have infantry, we don’t have enough artillery or shells. We don’t have enough drones.”

“The enemy has deployed powerful electronic warfare units so we sometimes have to launch 10, 12, 15 just to destroy one tank. If one of them was lucky enough to find the first EW vehicle, we could take out the rest.

“The situation is very complicated, and not in our favour. The most critical thing for us now is the large number of soldiers of the Russian Federation. They outnumber us I reckon by at least five to one.”

Russians ‘will be in city by mid-September’

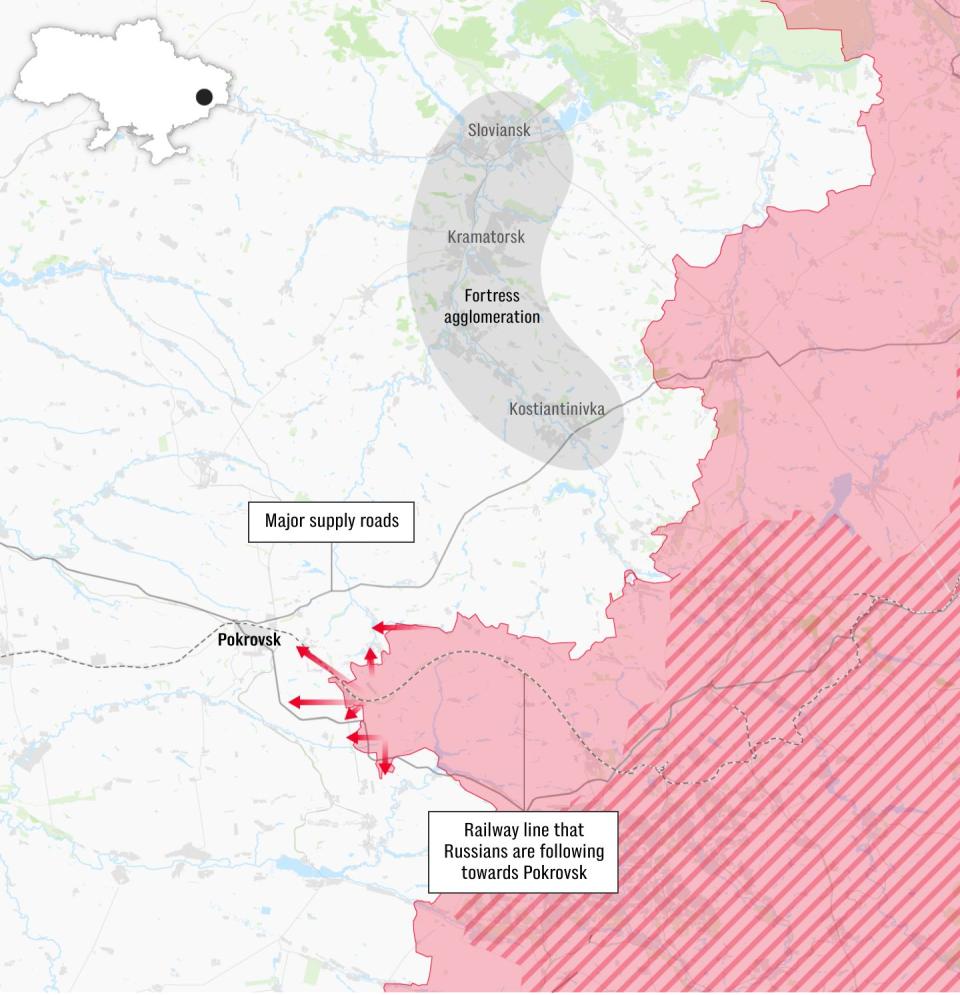

Over the past three weeks, the Russians have advanced at least five miles towards the city, moving along the cutting of a railway line that provides cover for their infantry.

By Tuesday, they had captured a third of Novohrodivka, a town astride that railway line. By Friday, Novohrodivka had fallen completely.

Battles are ongoing “on the left if you look from the enemy towards Pokrovsk” in an apparent attempt to bypass the suburb of Myrnohrad, where the urban environment might slow them down, the commander said.

“They are trying to break through this flank, basically along the track to the Pokrovsk, and they are succeeding and very successfully,” he added.

The Centre for Defence Strategies (CDS), a Ukrainian think tank, said in an assessment on Thursday that the Russians will probably reach the city by mid-September.

For Ukraine, that is not good news.

Pokrovsk is a strategic junction that sits on both road and rail links that sustain the Ukrainian garrison holding the front in other parts of Donetsk region. The most direct road between Pokrovsk and Kostiantynivka is already too dangerous to use and will probably be cut in the coming days or weeks.

If Pokrovsk falls, it will seriously complicate logistics for Ukrainian troops around Toretsk, Chasiv Yar, and the “fortress” agglomeration of Sloviansk, Kramatorsk, and Kostiantynivka.

The Russians are also expanding their salient on the flanks. On Thursday, fighting was reported on the outskirts of Selydove, a town south east of Pokrovsk.

To the east of the city, on the Ukrainian left, they have entered Krasnyu Yar and Hrodivka. Those moves threaten encirclement of large chunks of the Ukrainian front to the north, around Toretsk, and the south, around Kurakhove.

In other words, the Russians are poised to conquer a significant swathe of Donetsk region – one of their stated war aims – dangerously jeopardise the remaining Ukrainian footholds, and threaten an attack towards Dnipro.

Threat to city ‘direct result’ of Kursk operation

This desperate situation appears to be a direct result of Ukraine’s invasion of Kursk in early August.

That operation, planned by General Oleksandr Syrsky and greenlit by president Volodymyr Zelensky, was meant to draw Russian troops away from this front.

Gen Syrsky, the commander in chief of the Ukrainian armed forces, admitted this week that the Russians had not taken the bait.

While they have moved thousands of troops from other parts of the line to Kursk, on the Pokrovsk front they have doubled down.

Mr Zelensky testily defended the decision this week, arguing at a press conference that the Russians had been advancing on Pokrovsk even more rapidly before the Kursk operation.

That’s difficult to square with the accounts of officers and enlisted men on the ground.

CDS warned that in the Pokrovsk sector Russia enjoys a 4:1 advantage in forces, resources, drones and artillery, and that it could be assumed the Russians would reach Pokrovsk by mid-September.

The Ukrainian withdrawal from Norohrodivka, it noted, “indicates a lack of sufficient resources for defence, even on advantageous lines”.

Battle is not a foregone conclusion

The battle, however, is not a foregone conclusion.

Ukrainian sources claim the Russians are suffering record casualties in the Pokrovsk direction and that they will be unable to sustain the current pace of advance for much longer.

CDS predicted in its assessment that “the upcoming battle for Pokrovsk will be the climax of the enemy’s offensive operation on the southwestern theatre of war in 2024”.

Even some Russian war bloggers are uneasy, writing on Telegram that recent advances had been suspiciously smooth. Perhaps, they suggested, the Ukrainians are preparing some kind of trap?

The truth is few outside the Ukrainian and Russian high commands really know what is going on.

Could the Ukrainians be planning a stage two to the Kursk operation? Will the elite units who led the assault there be switched back to Donbas to hold the line? Will Ukraine fight for Pokrovsk, or retreat as it has done from outlying villages?

Or will the Russians be forced to switch reserves to Kursk after all, forcing them to halt? Are they plunging into an elaborate trap?

Or is it simply as it appears: an exhausted Ukrainian army finally buckling to the logic of superior Russian numbers?

“There is nothing positive to say, everything is difficult,” said the Ukrainian commander. “We are fighting and now we will see what kind of reinforcements there will be, if any, and then we will build defence on that. We’re trying to cut their main supply routes but they don’t stop.”

City shuts down ‘as if death is near’

Whatever the outcome, Pokrovsk itself is shutting down, like an organism that knows death is near.

A week ago, the supermarkets had closed but small shops were still open. Elderly women were still selling tomatoes, sunflower oil and milk on the main square every day. Locals queued at the social services office to collect their pensions as normal.

“Pokrovsk is changing in front of our eyes. Just two days ago there was some traffic, but today it was almost empty,” Roman Zhylenkov, a volunteer with the group Skhid SOS, which has been running evacuations from the town and surrounding front-line villages, told The Telegraph on Thursday.

“It’s not 2022 – there is no panic. People just pack their belongings, and shut down or relocate their business. There is information that banks will stop operating next Monday.

“The hospital is being relocated to Kryvyi Rih. After the hospital and local administration services are evacuated, locals will start moving out much faster.”

Sooner rather than later, the artillery and the drones will force even the most daring policemen and volunteers to give up on the rescue missions.

Everyone knows what comes next, because it has happened in so many towns before.

The elderly, the ill, and the very poor will be the last to leave, because they have nowhere to go. Some will refuse to move until it is too late. A handful of Russian sympathisers will probably stay behind to be “liberated”.

Windows will be blown in, the roads cratered, the houses destroyed. And then the armour and infantry will fight street-to-street through the rubble.

That is, if Ukraine fights for it. If the current rate of Russian advance continues, there may not be much of a battle at all.

Shortly after we spoke, Ms Korkh and her rescue dogs made it to the house in the Cherkassy region she and her husband had bought for such an emergency. Her husband is still in Pokrovsk.

“How do I feel?” she mused? “I can’t live happily in any other region.

“Yes, it’s my Ukraine, yes I love it, I’m not going to go to Europe or something. But for me, my Ukrainian Donbas…It’s my soul. I only wanted to live in Donbas. I only wanted to grow old in Donbas.”

She pauses to think, and then her voice finally cracks. “For me, it’s like my own, individual death.”