Scientists using ice-breaking ships and underwater robots have found the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica is melting at an accelerating rate and could be on an irreversible path to collapse, spelling catastrophe for global sea level rise.

Since 2018, a team of scientists forming the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration, has been studying Thwaites — often dubbed the “Doomsday Glacier” — up close to better understand how and when it might collapse.

Their findings, set out across a collection of studies, provide the clearest picture yet of this complex, ever-changing glacier. The outlook is “grim,” the scientists said in a report published Thursday, revealing the key conclusions of their six years of research.

They found rapid ice loss is set to speed up this century. Thwaites’ retreat has accelerated considerably over the past 30 years, said Rob Larter, a marine geophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey and part of the ITGC team. “Our findings indicate it is set to retreat further and faster,” he said.

The scientists project Thwaites and the Antarctic Ice Sheet could collapse within 200 years, which would have devastating consequences.

Thwaites holds enough water to increase sea levels by more than 2 feet. But because it also acts like a cork, holding back the vast Antarctic ice sheet, its collapse could ultimately lead to around 10 feet of sea level rise, devastating coastal communities from Miami and London to Bangladesh and the Pacific Islands.

Scientists have long known Florida-sized Thwaites was vulnerable, in part because of its geography. The land on which it sits slopes downwards, meaning as it melts, more ice is exposed to relatively warm ocean water.

Yet previously, relatively little was understood about the mechanisms behind its retreat. “Antarctica remains the biggest wild card for understanding and forecasting future sea level rise,” ITGC scientists said in a statement.

Over the last six years, the scientists’ range of experiments sought to bring more clarity.

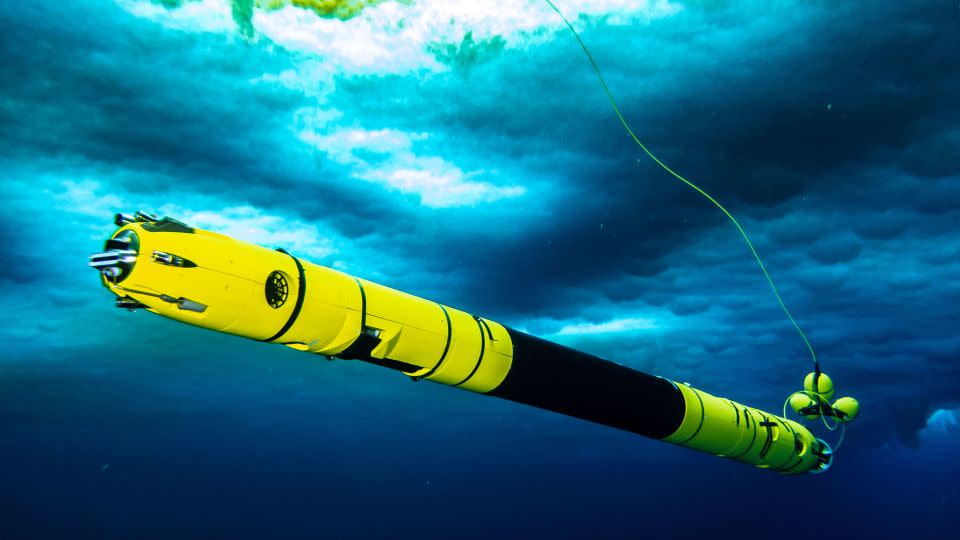

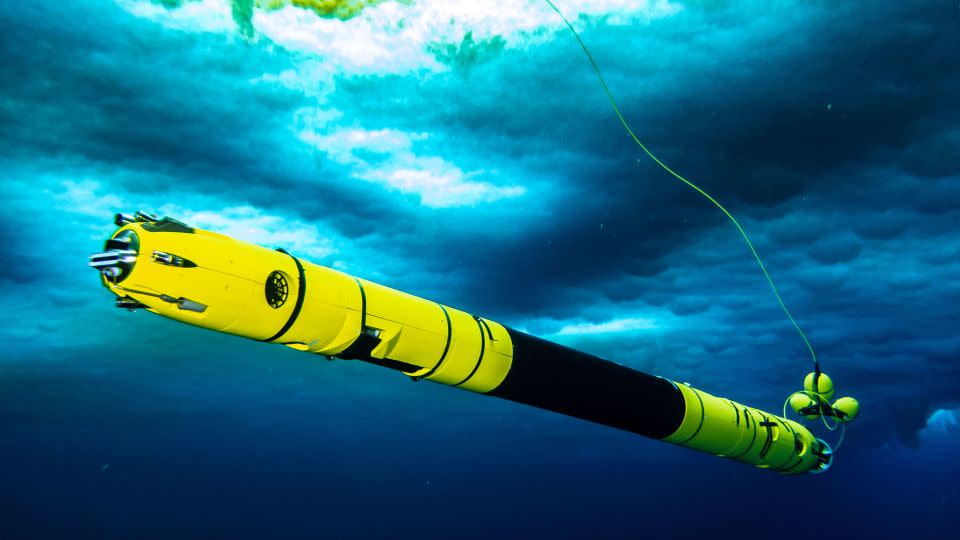

They sent a torpedo-shaped robot called Icefin to Thwaites’ grounding line, the point at which the ice rises up from the seabed and starts to float, a key point of vulnerability.

The first clip of Icefin swimming up to the grounding line was emotional, said Kiya Riverman, a glaciologist at the University of Portland. “For glaciologists, I think this had the emotional impact that perhaps the moon landing had on the rest of society,” she said at a new conference. “It was a big deal. We were seeing this place for the first time.”

Through images Icefin beamed back, they discovered the glacier is melting in unexpected ways, with warm ocean water able to funnel through deep cracks and “staircase” formations in the ice.

Another study used satellite and GPS data to look at the impacts of the tides and found seawater was able to push more than 6 miles beneath Thwaites, squeezing warm water under the ice and causing rapid melting.

Yet more scientists delved into Thwaites’ history. A team including Julia Wellner, a professor at the University of Houston, analyzed marine sediment cores to reconstruct the glacier’s past and found it started retreating rapidly in the 1940s, likely triggered by a very strong El Niño event — a natural climate fluctuation which tends to have a warming impact.

These results “teach us broadly about ice behavior, adding more detail than is available by just looking at the modern ice,” Wellner told CNN.

Among the gloom, there was also some good news about one process which scientists fear could cause rapid melting.

There is a concern that if Thwaites’ ice shelves collapse, it will leave towering cliffs of ice exposed to the ocean. These tall cliffs could easily become unstable and tumble into the ocean, exposing yet taller cliffs behind them, with the process repeating again and again.

Computer modeling, however, showed while this phenomenon is real, the chances of it happening are less likely than previously feared.

That’s not to say Thwaites is safe.

The scientists predict the whole of Thwaites and the Antarctic Ice Sheet behind it could be gone in the 23rd Century. Even if humans stop burning fossil fuels rapidly — which is not happening — it may be too late to save it.

While this stage of the ITGC project is wrapping up, the scientists say far more research is still needed to figure out this complex glacier and to understand if its retreat is now irreversible.

“While progress has been made, we still have deep uncertainty about the future,” said Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at the University of California, Irvine and part of ITGC. “I remain very worried that this sector of Antarctica is already in a state of collapse.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com