Rotting fish lay in the front yard. Sticky, foul mud lacquered everything. A lifetime’s worth of mementos — her daughter’s theater clothes, an old camera — were lost. Picking through the detritus, Silvia realized she could never return. She didn’t know where she would go. But this part of Porto Alegre, increasingly prone to cataclysmic floods, was no longer home.

“No, I can’t do this,” she said. “I can’t live with this fear of water, fear of rain.”

For years, scientists have warned that climate change would displace millions of people, reordering the world’s human presence as people searched for safety. The World Bank has estimated that more than 216 million people could be driven from their homes by sea level rise, flooding, desertification and other effects of warming temperatures. The Institute for Economics and Peace said the figure could reach 1.2 billion people. A future characterized by “climate refugees,” the European Parliament reported, was coming.

GET CAUGHT UP

Summarized stories to quickly stay informed

That future now appears to have arrived. Floods in Pakistan in 2022 displaced an estimated 8 million people. Floods in Ethiopia in 2023 and Kenya this year forced hundreds of thousands more from their homes.

“Brazil is not going to be a one-off,” said Andrew Harper, a senior official at the U.N. High Commission for Refugees. “What we are seeing is the start of something that will become more frequent and more extreme and lead to more people left vulnerable, with no choice but to move to a safer location.”

The floodwaters that surged here late last month swept nearly every municipality in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul. Whole cities remain submerged. Areas that were spared have absorbed hundreds of thousands of displaced people. Many say they have no desire to return to homes they believe are unsafe. Officials now openly discuss the once-inconceivable: the relocation of entire towns to higher ground.

The disaster, Brazilians say, has the makings of a historic pivot point, when the Western Hemisphere’s second most populous country is forced to address its climate vulnerability by rethinking where and how it lives.

“We’re going to have to change our geography,” said Jairo Jorge, mayor of devastated Canoas. “The situation has changed. This will only get worse.”

Silvia Titton, wearing a mask to dilute the stench as she rummaged through a mess of ruined possessions, was already thinking these thoughts.

A neighbor who’d come to inspect the wreckage of his home saw her and shouted.

“You’ve returned?” he asked.

“No,” Titton said. “I’m not returning.”

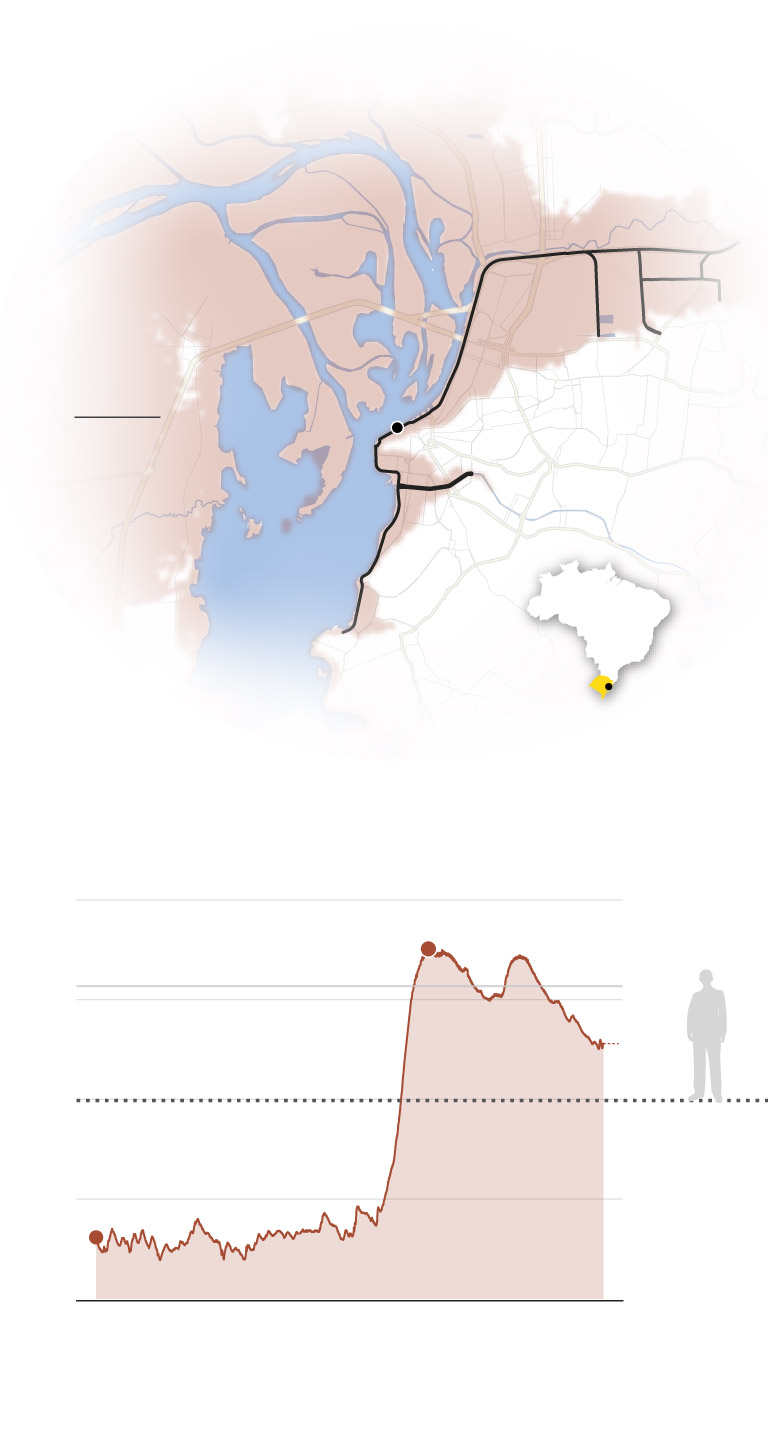

A city left vulnerable to climate change

Rain patterns in Brazil are changing. The verdant Amazon rainforest is increasingly wracked by drought. Stretches of the country’s northeast have been classified for the first time as arid. And across the south and southeast, rainfall has increased in both volume and intensity, unleashing deadly landslides and repeatedly flooding Porto Alegre.

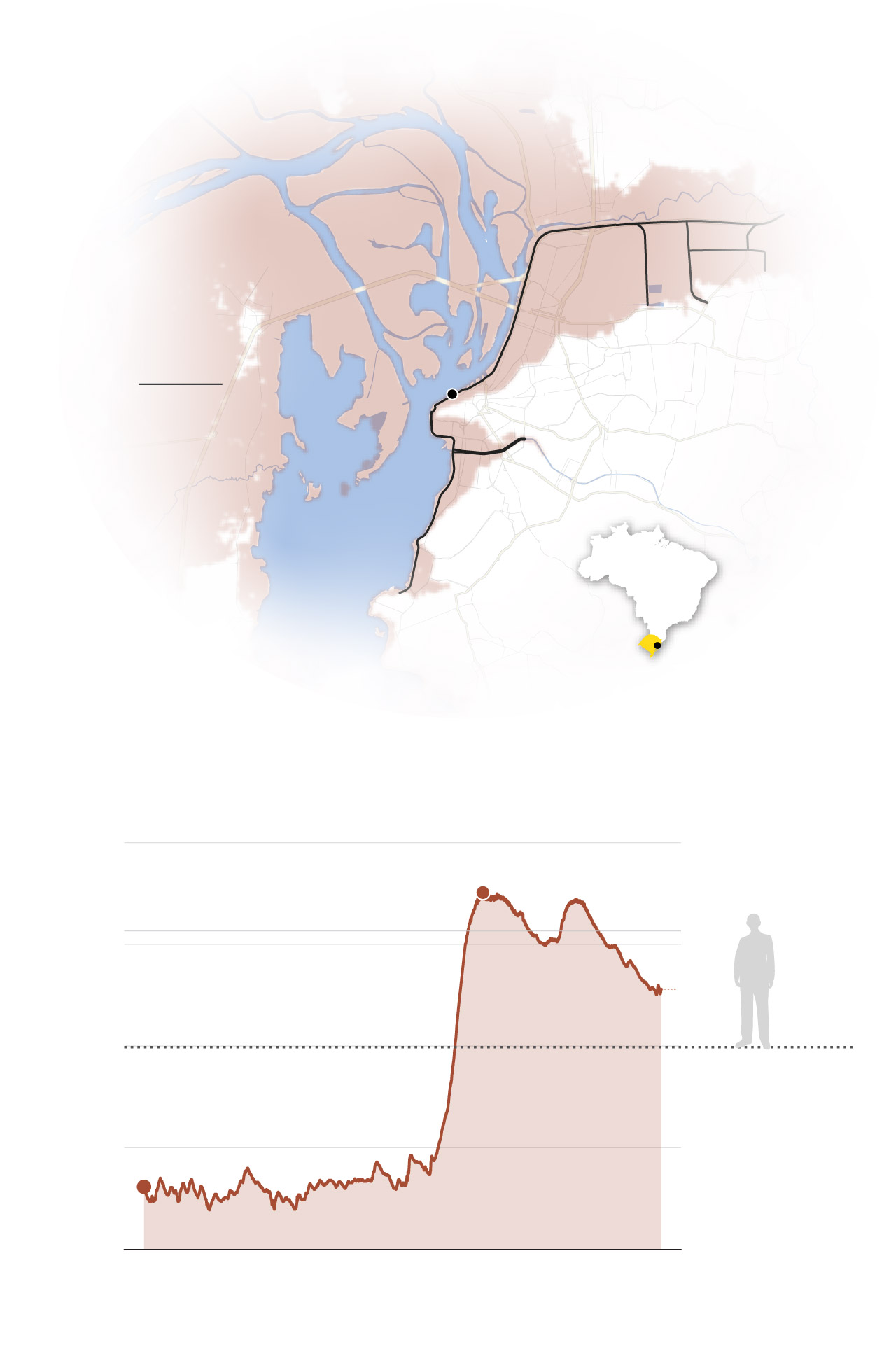

Water level at the Mauá Pier in feet

Previous record

high in 1941

River overflows

above this level

As of 11:15 a.m. Eastern, May 23

Water level at the Mauá Pier in feet

Previous record

high in 1941

River overflows

above this level

As of 11:15 a.m. Eastern, May 23

Water level at the Mauá Pier in feet

River overflows

above this level

As of 11:15 a.m. Eastern, May 23

The security of this city of 1.3 million is undermined by its geography. Its sprawl, which concentrates half the state’s population, lies at the topographical equivalent of a funnel. Rivers from the mountains above converge in the lowlands of Porto Alegre, where interlinking lakes carry the water out to the ocean.

The risk was contained, for a time, by a system of levies and dikes. But in recent decades, as basic maintenance of the system faltered, and agricultural practices stripped away the region’s barrier forests, and climate change ushered in ever more devastating rains, the city has become one of Brazil’s most vulnerable.

It was into these conditions that, late last month, a hard rain began to fall. Within two weeks, more fell than had been predicted for an entire five-month period. The waters gushed down into the Porto Alegre basin, where the antiquated hydraulic system failed. With only one exit — through the Lagoa dos Patos to the ocean — the deluge stagnated, a toxic brown stew.

The mayor of Porto Alegre, Sebastião Melo, has been criticized for the failure to maintain a levy system that analysts say could have averted 80 percent of the city’s flooding. Melo said the system, built in the 1970s, was never intended to contain so many floods. Rio Grande do Sul has been hit by three in the past year alone.

“The system needed a $1 billion to fix,” he told The Washington Post. “I invested as much as I could, but I didn’t have $1 billion.”

Hospitals shut down. The airport closed. People were stranded on rooftops for days. Looters stole at will. Criminals gangs moved drugs with impunity. Stores were ransacked for bottled water. The one passable road out of the city was clogged by traffic jams miles long. More than 80,000 people surged into hastily arranged shelters for the displaced.

“Many of these people are never going to return home,” Melo said. “It’s no use for them to go back to the same areas.”

Daniel Jesus Ventura agreed. The 33-year-old electrician was sheltering with his family at a university. His wife wanted to go back and see their wooden lake house. But he didn’t see the point. The waters had surely claimed it.

He wanted off the water, out of southern Brazil.

“This is only going to get worse,” he said.

‘There’s no way we can live like this’

A team of disaster responders steered a motorboat through an impoverished neighborhood in the saturated suburb of Canoas. Cars, homes, everything lay under muddy water that health officials warned was likely to carry disease. The carcass of a horse bobbed in the murk.

“That’s just the beginning,” said Jenifer da Silva, one of the responders. “Once the waters drop, we think we’re going to find a lot of dead people. Mostly the old.”

They didn’t know what kind of city would emerge. Only that it would be different.

“The wooden houses of the poor will absolutely be destroyed,” said Igor Sousa, a fellow responder. “When the water falls, they’ll take them all down.”

Where the people of Canoas and other cities will go is unclear. For now, hundreds are reported to be living in tents or in cars or underneath a bridge. Tens of thousands more are in shelters for the displaced. Many more with relatives.

The floods may soon recede. But the humanitarian crisis is only beginning.

State officials want to construct four large camps for the displaced. One in Porto Seco — Dry Port — where authorities have announced plans to raise 5,000 tents and shelter 10,000 people for a year.

That could give officials time, vice-governor Gabriel Souza said, to study Rio Grande do Sul’s geography and determine which communities should be moved.

“We cannot build the same things in the same way, in the same places,” he told The Post. “We do not rule out having to relocate entire neighborhoods and cities.”

Others have decided not to wait around to learn what government officials have in store.

Rafael Barbosa, 30, sat in a flood shelter, planning his move.

“I’m leaving for Goiás,” he said, a faraway state in central Brazil. His reasoning, he said, was simple: “We know it, and there aren’t any floods.”

Nearby, Rafael Vitor de Arruda Aquino, 18, was already packing his things. He’d secured a seat on a government-funded flight to Amazonas state. That would now be home for him and his girlfriend, Thaiciele Silva de Castro, 16.

“There’s no way we can live like this,” Aquino said.

His mother began to weep. She had decided to stay in Porto Alegre, where she has work.

“I’m not going to make it here,” she said. She watched them head for the door.

“We’ll wait for you up there,” Thaiciele said.

Then they were off, for a new life in a state where they hoped would be safe.